The Dullahan: old origin legends of Ireland's headless horseman

Ever since I first saw Sleepy Hollow as a teenager I’ve been haunted and fascinated in equal measures by stories of headless horsemen.

And, as I have Irish heritage, stories about the death-bringing Dullahan intrigue me even more.

So here’s a rundown of this ominous creature - apparently categorised as an evil or dark fairy - along some creepy old origin legends I dug out of the history books.

Published: 19th Apr 2025

Author: Mythfolks

What is the Dullahan?

The Dullahan - also called Durrachan or Dullahav in various Irish dialects - is a type of supernatural being in Irish folklore, most commonly recognized as a headless rider.

The name itself may derive from dorr or durrach, meaning "angry," "malicious," or "fierce," though others suggest it includes the word dubh ("black") as a root.

The appearance of the Dullahan supposedly signals that someone nearby is about to die. The creature is often described as riding a black horse - also headless - and carrying its own severed head under one arm. Lovely.

In some tales, it drives the Death Coach, or Coach-a-bower, a ghostly carriage pulled by headless horses, racing silently through the night.

Belief in such headless figures isn’t of course confined to Ireland. Similar apparitions exist in Welsh folklore (the Ceffyl heb un pen - headless horse - and Fenyw heb un pen - headless woman) and English and Scottish legends also record headless phantoms, particularly during times of unrest or tragedy.

The Dullahan has even been compared to ghost stories in France and Spain, where headless coaches and skeletal horses are also seen as death omens.

Though often terrifying, the Dullahan doesn’t always harm those who see it - but it never speaks except to call the name of the one doomed to die. So it acts more like a messenger of death rather than the cause.

4 old origin legends about the Dullahan

The Headless Horseman

Charley Culnane was riding home late one December night after a long day in Fermoy, where he’d been buying Christmas dinner supplies and getting new snaffle reins fitted to impress the hunting crowd on St. Stephen’s Day.

After a few too many drinks with his friend Con Buckley in Ballyhooley, Charley finally bolted and mounted his mare for the rainy, pitch-black ride home along the banks of the Blackwater.

He sang as he went, rain soaking his fancy new reins, when the mood shifted. Near Kilcummer Hill, he noticed something strange: the head of a white horse floating beside him - no body, no rider.

Then, without warning, the body appeared, massive and mounted by a figure over eight feet tall, dressed in an old scarlet hunting coat. The figure had no head or at least not where it should be. Charley kept sneaking glances and eventually spotted the grotesque head tucked under the rider’s right arm, staring at him with glowing eyes and a wide, horrible grin.

Despite the terror, Charley, always one for a good race, tried to make conversation, but the replies were short and gruff. Eventually, they spoke more freely and the headless horseman challenged Charley to a ride across country.

Charley agreed without hesitation - he had a hundred-pound bet riding on his mare beating a rival’s horse in the upcoming hunt. They leapt over walls and ditches at full tilt, Charley just ahead. When he pulled up, the horseman admitted he’d been searching for a brave rider for a hundred years - someone who wouldn't back down. Charley had passed the test.

Just like that, the horseman vanished into the air, his head stuffed into his coat pocket. Charley, stunned, went home and told everyone - his wife, the neighbours, the hunt. No one believed him.

They blamed the whole story on Con Buckley’s over-proof whiskey. Still, on St. Stephen’s Day, Charley’s mare beat Desdemona and he won his hundred pounds. Whether it was skill or a ghostly blessing, Charley never said - but he never forgot the headless horseman.

The Good Woman

In a quiet valley beneath the Galtee Mountains lived Larry Dodd and his wife Nancy, a content and capable couple who worked their small farm with care. Larry was short, broad, and often ruddy-faced, known both for his horse-breaking skills and his fondness for drink.

Larry cut a half-jockey, half-farmer figure as he rode home from Cashel one June evening, pleased with his purchase of a rough-looking but sound horse.

As twilight settled, a cloaked woman appeared beside him, walking fast and silent. Larry, ever the gentleman, offered her a lift behind him. She accepted without a word, leaping lightly onto the horse.

The journey was quiet. She held onto Larry without speaking, and they soon reached a dark patch of road near a pool shaded by old ivy-draped trees. When the horse suddenly halted, Larry got down to check a loose shoe.

The woman slipped off behind him without a sound and darted across a field toward the ruins of Kilnaslattery church. Larry gave chase, half teasing and half flirtatious, calling after her. She moved swiftly, gliding over the brambles and tombstones like the overgrown graveyard was a ballroom floor.

Just as she circled the church again, Larry lunged forward to catch her—only to find himself embracing a woman with no head.

Paralyzed with fear, he stumbled into the ruined church, where a strange light illuminated a torture wheel adorned with human heads.

All around, well-dressed figures - soldiers, priests, townsfolk - danced headless in a grisly revel, their skulls tucked under arms or bowled across the floor by skeletal onlookers. Bells clanged, bones rattled, and the great bell of the church tolled solemnly.

One of the dancers handed Larry a drink. He accepted it, raising the cup to his lips, but before he could speak, he too was beheaded, his head flying loose to join the dance.

When Larry awoke, it was broad daylight, and he lay on the cold floor of the ruined church, his head miraculously still on his shoulders. Sore and shaken, he found his horse gone and trudged home, dreading Nancy’s reaction. She scolded him, of course, especially after hearing about the lost horse and the seven IOUs.

When she asked why he’d gone off-road toward the church, Larry, caught without a good lie, finally muttered that it had been “a young woman without a head.” Nancy erupted in grief and fury - "a woman without a head!" she cried. But Larry, regaining some of his bravado, declared that any woman without a tongue might rightly be called a Good Woman.

Whether that calmed his wife or not remains unknown, though it's said she had the last word.

Hanlon’s Mill

One summer evening, Michael Noonan took a quiet walk along the river toward Ballyduff to pick up his brogues from the shoemaker, Jack Brien.

The path led past the old Hanlon’s mill, now long abandoned. The mill, seemed haunted by its former life, the old wheel black with age, motionless as the stream flowed uselessly by.

As Michael neared the ruins, the air filled with the sudden sound of horns, barking hounds, galloping horses and a huntsman shouting commands, all echoing back from the far bank.

Yet he couldn't see anything. The noise followed him all the way to Jack Brien’s door, along with what he swore was the clacking of the old mill wheel - long still and rotted.

At the shoemaker’s, Michael was relieved to find not only his repaired brogues but also his neighbor, Darby Haynes. Darby asked if Mick would take his horse and cart home, since he was waiting for his nephew.

Mick agreed, glad for the company of a horse and the excuse to avoid the mill. The night was calm, the moon high and bright. Mick relaxed on the cart, watching its reflection in a roadside puddle, when suddenly the light vanished.

Looking up, he saw beside him a tall black coach drawn by six black horses, all headless, with a headless coachman perched silently above.

The wheels spun quickly, the horses moved with unnatural smoothness, but there wasn’t a sound - only the creak of Darby’s cart and the faint squeal of unoiled axles. The coach passed swiftly and disappeared among the trees without a trace.

Mick made it home safely, put away the horse and tried to sleep. The next morning, still unsettled, he stood at the roadside when Dan Madden, huntsman for Mr. Wrixon, galloped toward him in distress.

Mick stopped him and asked what had happened. Dan, nearly breathless, said the master had taken suddenly ill, collapsed without warning and was now barely holding on.

Mick ran off to fetch Kate Finnigan, the local midwife known for her skill, while Dan rode for the doctor. But neither of them arrived in time.

That night, under the same fading moon, Ballygibblin became a house of mourning. Mr. Wrixon, who had been strong and well the day before, was dead.

And Mick, with the clack of a ghostly mill and the sight of a silent, headless coach still fresh in his mind, had no doubt about what he’d seen.

The Death Coach (retold from the ballad)

It was just past midnight. The sky was black, not a star to be seen. Somewhere in the distance, a low rumbling began. It rolled closer, louder, faster, until the ground itself seemed to shake. Then it came into view: a black coach, moving at full speed.

There was no head on the driver. No heads on the passengers. The six horses pulling it were headless too. The wheels spun fast, their spokes made from dead men’s thigh bones. The coach pole was a human spine. A tattered funeral pall hung where the cover should and two hollow skulls swung at the front, glowing like lanterns.

It raced down from Rathcooney churchyard, tore through Glanmire, flew past Lota. It didn’t slow for anything. Steep hills meant nothing to it. The Dullahans inside—soldiers, priests, jockeys—leaned back in silence as the headless coachman whipped the horses on. They didn’t stop in Cork. They shot through the city and out again without a pause.

By the time they reached Ballintemple graveyard, it was past midnight. The coach stopped. The passengers got out. A voice came from the ground: “There’s no room.”

One of the Dullahans answered, “We’ve come from the parish of Skull.” The graveyard was full - Murphys, Crowleys, Fitzgeralds, Toonies - but they made space.

“We’ll lie here tonight,” the Dullahans said. “In the morning, we’re off to find the Old Head of Kinsale.”

As a horror fan, i loved these stories. But I especially love the thoroughly Irish flair that comes shining through in every legend.

If you like these kinds of creepy stories about the appearance and disappearance of weird creatures and ghosts then you'll also enjoy a trip over to some Latin American folklore and the story of La Carreta Chillona or the screeching wagon.

Article sources

- Croker, Thomas Crofton. Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. 3rd ed. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street; and William Tegg & Co., 73, Cheapside, 1846

Explore more folklore

From ancient mythology through the witch craze of the Middle Ages and beyond, get an overview of our history with witches here.

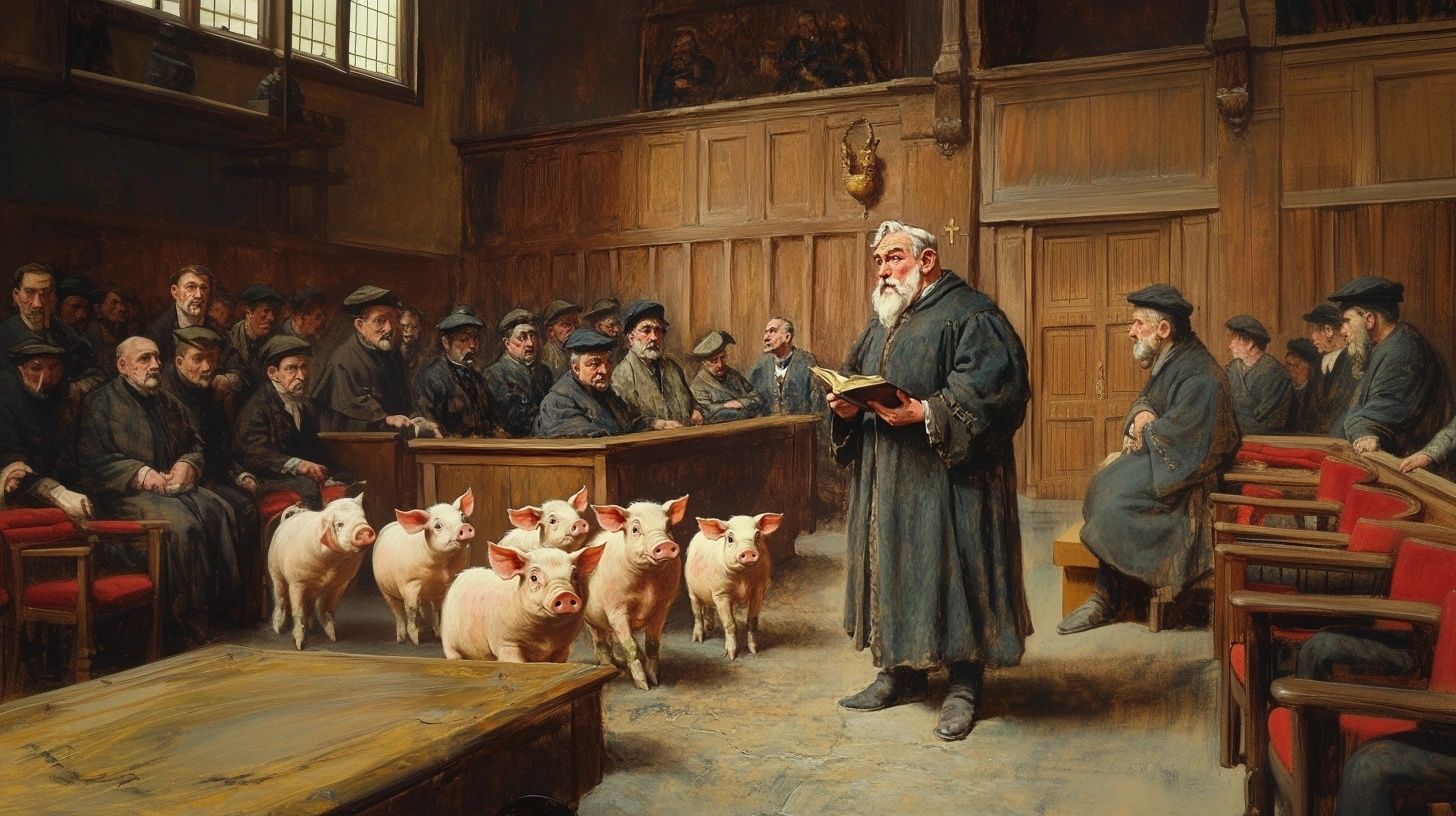

Discover the time when animals were put through real human trials - with lawyers and everything...

Explore US folklore

11 US ghost towns that are actually haunted

Maybe...if you like escaping the crowds, these towns are not only abandoned but largely unvisited by tourists. Check them out.