Scottish folklore creatures, legends &

fairy tales

Scotland has always been a land steeped in mystery, legend and superstition.

From fantastical mythical creatures and fairy tales, to heroic legends and Scottish witchcraft history, these folklore stories are as old as the hills themselves.

So, whether you’re looking to learn a bit more about this great country's folk history, a Scot looking to reconnect with your roots or perhaps you're looking for some creative inspiration for your next book, sit back and enjoy these stories.

Updated: 2nd Jan 2025

Author: Mythfolks

Scottish mythical creatures

Shapeshifters

Selkies

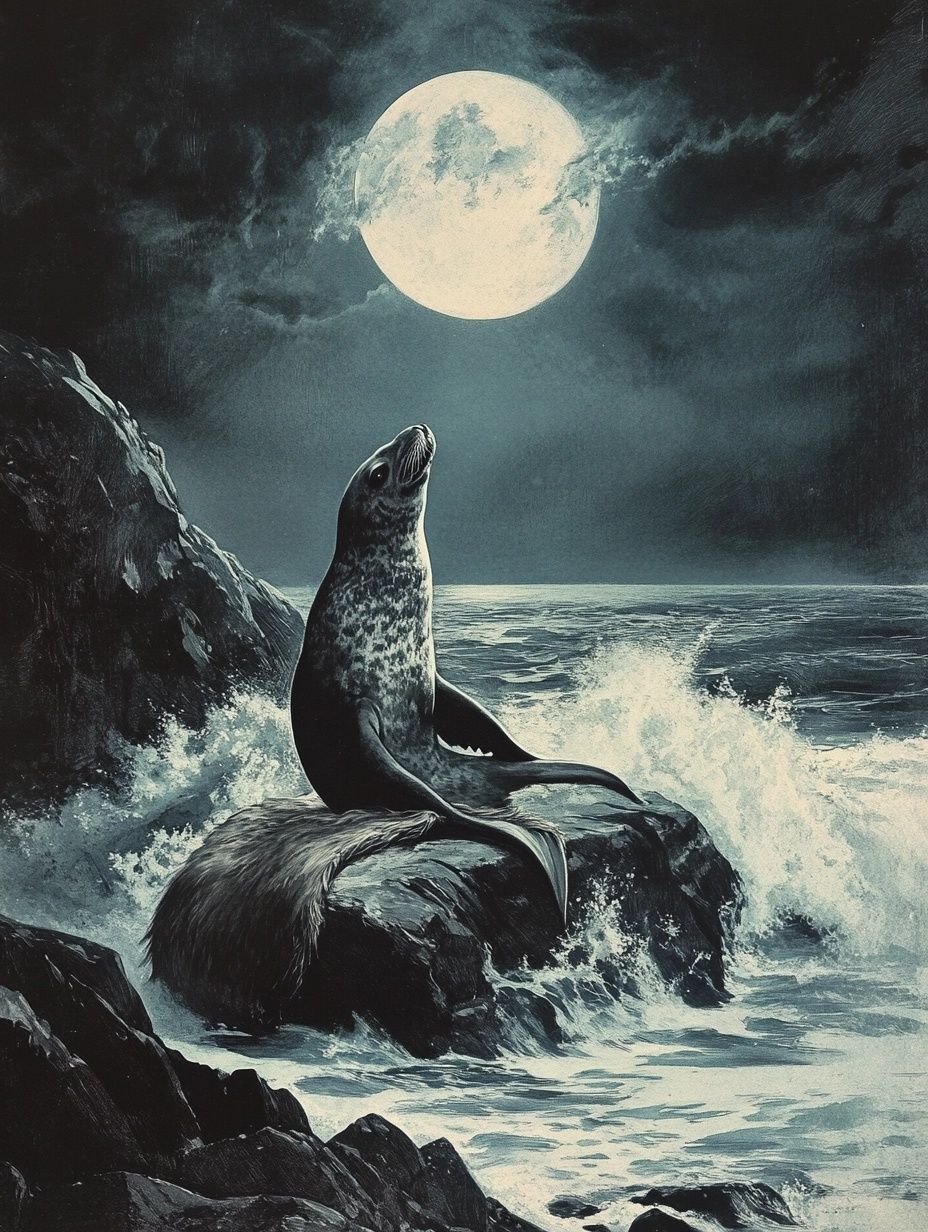

Selkies in Scottish folklore are shapeshifters capable of moving between the worlds of land and sea.

In their natural form, they appear as seals, but they can shed their skins to reveal a human form. The stories surrounding Selkies are often bittersweet, tinged with themes of longing, loss and the struggle for freedom.

One of the most famous Selkie tales involves a fisherman who discovers a Selkie’s skin on the shore.

Curious and captivated by the creature’s beauty, he hides the skin, trapping the Selkie in human form. With no choice but to stay, the Selkie marries the fisherman and bears his children.

Despite living a seemingly happy life, the Selkie never stops longing for the sea.

One day, she finds her hidden skin and, without hesitation, returns to the ocean, leaving behind her family and the life she built on land.

These folktales often portray Selkies as tragic figures - caught between two worlds, they’re never fully at home in either.

The Selkie’s longing for the sea can also be seen as a yearning for authenticity and freedom, a theme that resonates in a world where many of us feel pressured to conform to societal expectations.

Kelpie

Kelpies are another shape-shifting creature from Scottish folklore, but their nature is much darker than that of the Selkies.

A Kelpie is an evil water spirit whose most common form is that of a beautiful, tame horse, often with a wet mane that entices weary travelers to mount it.

Once the victim is on its back, the Kelpie charges into the water, drowning its rider and devouring them in the depths.

But the Kelpie isn’t confined to just one form. Some tales describe the Kelpie as being able to transform into a handsome young man to lure women to the water’s edge, where it reveals its true nature.

Regardless of its form, the Kelpie’s intent is always sinister - these creatures embody the dangers that lurk in the natural world, particularly in the waters of Scotland’s rivers and lochs.

Boobrie

The Boobrie in Scottish folklore is described as an unknown water bird that’s sometimes associated with the Kelpie or Water Horse due to its reported ability to shapeshift.

Found in regions like Argyll and Bute, the Boobrie is said to resemble a large loon with white streaks on its neck and breast, a long, eagle-like bill and webbed, clawed feet. Its call is likened to the roar of an angry bull and it’s said to live in isolated lochs and marshes and feed on lambs and otters.

Some stories suggest that it can transform into various aquatic creatures or even a giant insect, to lure its prey similar to other tales of Scottish shape-shifting creatures like kelpies.

While there are attempts to explain the Boobrie as a misidentified bird, such as the Yellow-billed Loon, its supernatural attributes, particularly its shapeshifting abilities and predatory habits, firmly root it in the realm of folklore.

The Boobrie is yet another tale in the Scottish tradition of mysterious water creatures.

Ghosts & spirits

Nuckelavee

The Nuckelavee is an evil sea spirit from Orcadian folklore (from the Orkney Isles in Northern Scotland), considered to be a bringer of disease, famine and misfortune.

It’s described as a grotesque hybrid creature, blending elements of horse and man into a single, horrifying form. Its horse-like body has flippers for legs, a massive gaping mouth and a rider-like humanoid figure fused to its back.

The most terrifying detail is its skinless body, revealing raw, pulsating flesh, blood vessels and sinews, making it an unmistakable figure of terror.

This creature’s mythology highlights its connection to environmental and social calamities. Its breath is said to carry venom capable of withering plants and bringing disease to both humans and animals.

Despite its destructive nature, the creature has some vulnerability - it can’t tolerate fresh water and is unable to cross streams or rivers. This weakness provides a rare means of escape for those unfortunate enough to encounter it.

Folklore surrounding the Nuckelavee also portrays it as highly territorial, with a strong aversion to humans entering its domain.

The Bean Nighe

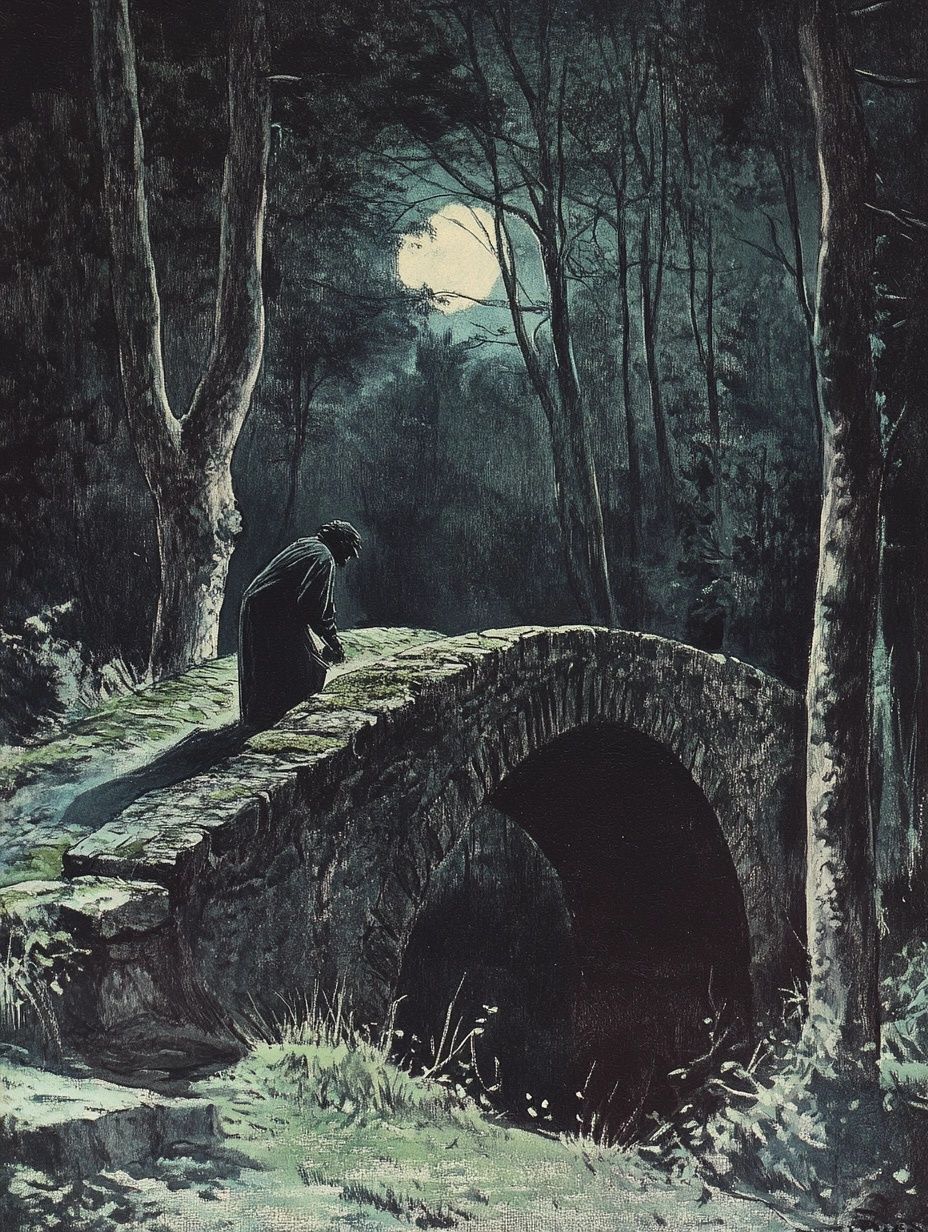

The Bean Nighe, or “Washerwoman,” is a ghostly figure in Scottish folklore and is often described as a woman seen washing bloodstained clothes or armor at the edge of a river or loch.

According to legend, the Bean Nighe is an omen of death - those who encounter her are either destined to die soon or are witnessing the foreshadowing of someone else’s demise.

The Bean Nighe is sometimes depicted as a haggard old woman with a ghostly pallor, but other stories describe her as a more neutral figure, simply performing her grim task without malice.

In some versions of the myth, if a person approaches the Bean Nighe and speaks to her respectfully, they might be able to gain insight into their fate or even alter it.

However, this is a rare occurrence, as most who encounter her are too paralyzed by fear to even consider such an action.

The origins of the Bean Nighe likely stem from the ancient Celtic belief in the Banshee, another female spirit whose wailing heralds death.

This story can similarly be seen as a reflection on the inevitability of death and the ways in which different cultures grapple with mortality.

The Bogle

The Bogle is a spirit from Scottish folklore, known for its mischievous and often nasty behavior.

Unlike creatures that harm outright, bogles primarily aim to confuse, scare, or frustrate humans, thriving on trickery and deception.

One notable variation is the Shellycoat, a water-dwelling Bogle whose name comes from the clattering shells it wears.

This unique detail highlights the playful, if unsettling, nature of the creature, as its shell-covered appearance is as distinct as the pranks it performs.

Bogles are infamous for their ability to lead humans astray. In one tale, the Shellycoat mimics the cries of a drowning person, luring travelers on a wild and exhausting chase along a river.

When the victims realize the deception, the Bogle laughs uproariously at their expense. These antics highlight the bogle’s role as a spirit of mischief, one that delights in toying with human expectations without necessarily causing physical harm.

While often tied to specific locations like rivers, Bogles can also haunt old buildings and desolate areas.

Fatlips

Fatlips is a supernatural figure from Scottish folklore, said to haunt the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey.

Described as a small being wearing heavy iron shoes, Fatlips was believed to roam the vaults, stamping across the stone floors with an ominous clatter.

While there are no accounts of Fatlips harming anyone, the presence of this spirit created an atmosphere of dread, leading local villagers to avoid the area, especially at night.

The origins of Fatlips are tied to the tragic story of a woman who lived in the abbey ruins. This woman claimed to be in communication with the spirit, whom she described as her guardian or companion during her self-imposed exile.

Her reclusive life and unwavering belief in Fatlips blurred the lines between her personal tragedy and local folklore, giving rise to the legend of the creature.

Over time, Fatlips became less about the woman herself and more a part of the abbey’s haunted reputation.

Big Grey Man of Ben Macdhui, or Am Fear Liath Mòr

The Big Grey Man is a mysterious entity reported on Ben Macdhui, Scotland's second-highest mountain in the Cairngorms.

Considered by some to be a cryptid (but with more characteristics of a supernatural being), it’s described as a giant figure, between 10 and 20 feet tall, with broad shoulders and long, waving arms. The Big Grey Man is often associated with a sense of unease rather than direct sightings.

One of the most famous accounts comes from 1891, when mountaineer Norman Collie described hearing footsteps crunching behind him as though something massive was following, mirroring his pace.

In 1942, Sydney Scroggie, camping on the Cairngorms, reported seeing a large, stately figure walking through the fog.

Physical evidence, such as large footprints measuring 19 inches long, has also been reported, adding to the mystery.

Explanations for the Big Grey Man range from natural phenomena to psychological effects.

The Brocken spectre, an optical illusion where an observer's shadow appears large and surrounded by a halo of light, is one theory.

Others suggest the high altitude and harsh conditions of Ben Macdhui could trigger hallucinations or heightened senses, causing people to misinterpret natural sounds and sights.

Goblins, fairies & brownies

Fairies in Scottish folklore

Scottish folklore fairies, sometimes known as the "Little Folk" or "good neighbors," are tied closely to nature and the spirit world.

They were believed to live in mounds, hillocks, or hidden glens and were renowned for their love of music and dancing.

Fairies had unpredictable relationships with humans, sometimes helping by teaching skills or performing household tasks but just as often causing harm.

They were feared for their ability to curse, steal cattle and lure people into their realm.

Specific types of fairies include the "Ly Erg," a red-handed soldier-like spirit who challenged people to duels, and "Meg Mullach," a small, hairy household helper and the Ghillie Dhu (see next story).

The origins of fairies in Scottish lore vary. Some stories describe them as an ancient race driven into hiding in caves and burial mounds by invaders, while others suggest they're old Celtic nature spirits or gods, remembered in diminished form.

Christian interpretations sometimes frame them as fallen angels who remained neutral during a heavenly rebellion and were cast to Earth, existing between good and evil.

The Ghillie Dhu

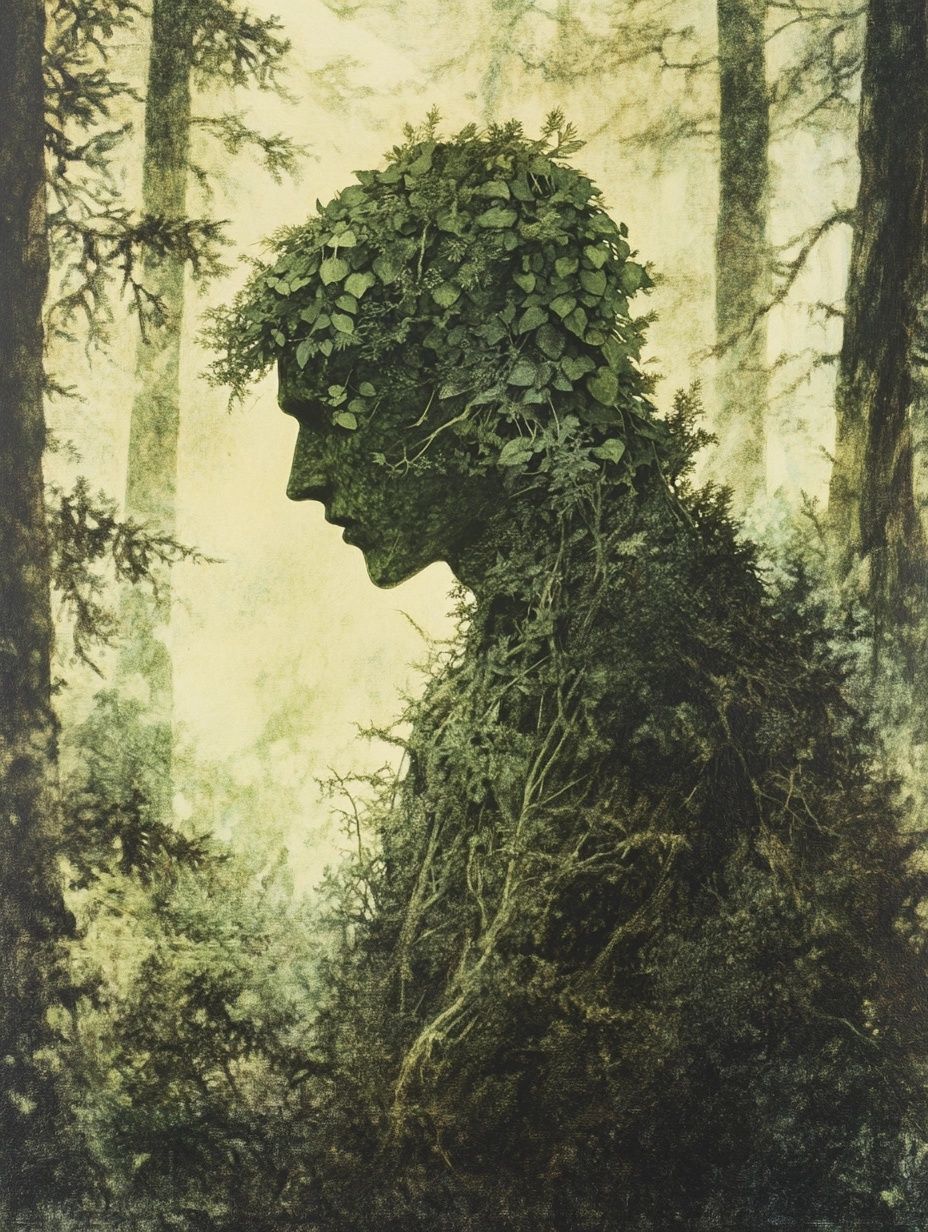

The Ghillie Dhu is a lesser-known figure in Scottish folklore, a solitary fairy known for its deep connection to the forest.

This creature, often described as a small, dark-haired figure clad in leaves and moss, is said to live in the woods of the Scottish Highlands, particularly around Gairloch in Ross-shire.

The Ghillie Dhu is a protector of the trees and is believed to be both shy and kind, especially toward children and those who respect the natural world.

Legends tell of the Ghillie Dhu helping lost travelers find their way out of the forest or guiding those in need to safety.

However, it’s also said that the Ghillie Dhu can be fiercely protective of its territory, showing a darker side to those who seek to harm the woods.

This dual nature reflects the delicate balance between nature’s kindness and its capacity for retribution when mistreated.

Redcap

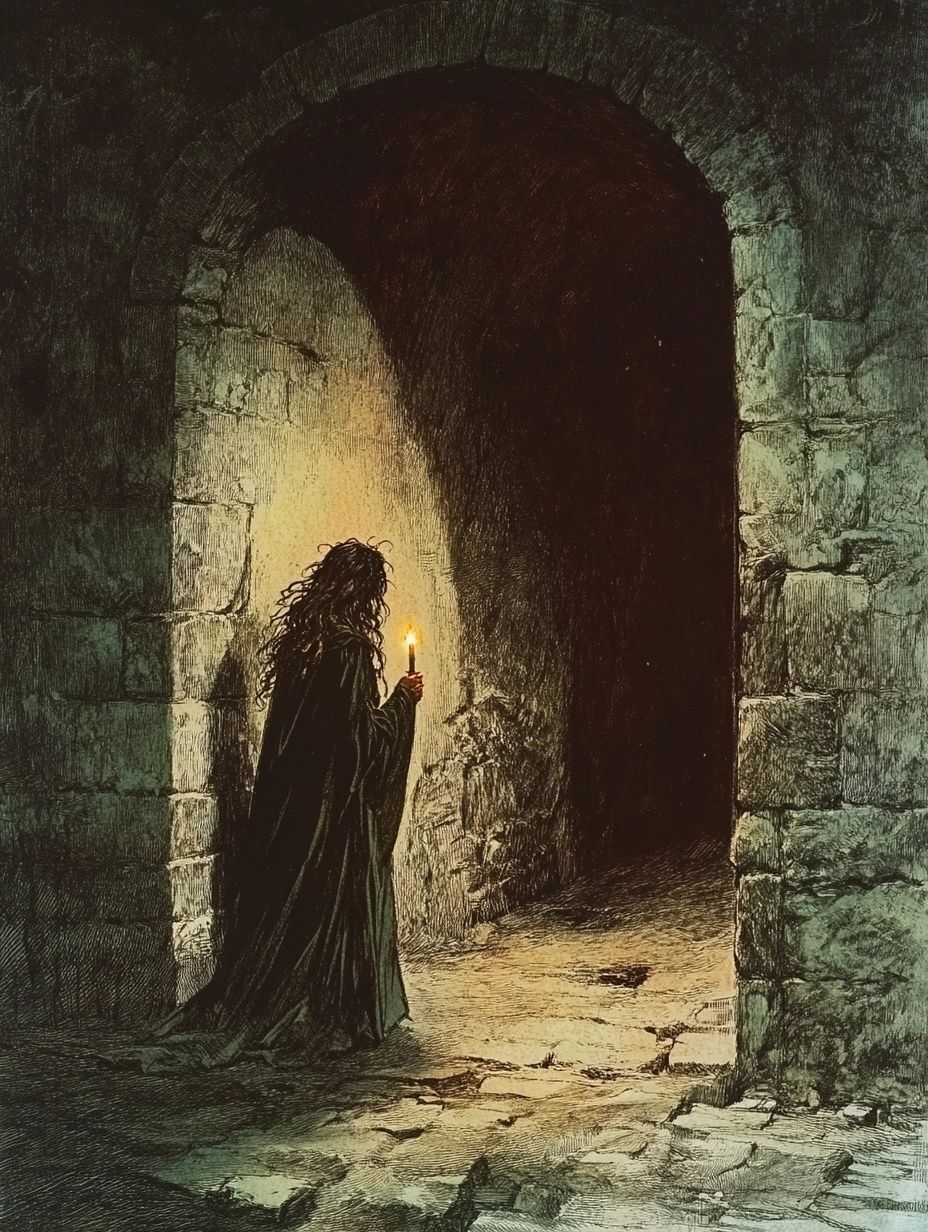

The Redcap is one of the more sinister figures in Scottish folklore, an evil goblin said to live in the ruins of castles and fortresses, particularly those that have seen bloodshed.

This fearsome creature is named for the red cap it wears, which is said to be soaked in the blood of its victims.

The Redcap is a small, shriveled figure with iron boots and claws for hands, and it is known for its murderous nature and unrelenting pursuit of those who dare trespass on its territory.

The Redcap’s gruesome reputation is tied to its habit of killing intruders and using their blood to dye its cap. If the blood begins to dry out, the Redcap is said to weaken, driving it to commit more violence to keep its cap fresh.

The legend of the Redcap likely originates from the darker aspects of Scotland’s turbulent history, where many castles were the sites of violent conflicts.

The Redcap serves as a reminder of the past and the lingering presence of evil in places where terrible deeds were committed.

Scottish Brownie

The Scottish Brownie is a supernatural household spirit known for its hardworking and helpful nature, distinct from the mischievous or dark tendencies of other fairies. Brownies are described as small, shaggy and wild in appearance.

They live in hidden corners of homes or barns, working at night to complete tasks such as cleaning or farming that benefit the household they choose to serve.

However, Brownies also display a strong sense of pride. They demand no direct reward for their labor and offering them payment - especially food or clothing - will almost always cause them to leave permanently.

Unlike other fairies, the Brownie’s attachment to the families they help is based on loyalty rather than mischief or trickery. Tales of the Brownie often emphasize its dedication and resourcefulness.

For example, a Brownie might take great risks to assist in emergencies, such as retrieving a midwife for a laboring woman or performing arduous chores.

Animals & humanoids

Wulver

The Wulver is a creature from Shetland folklore that is sometimes mistaken for a werewolf. Described as a man with a wolf’s head, the Wulver exists in this state permanently, rather than transforming like werewolves from other myths.

He’s also said to be a kind, solitary figure who lives in a cave and spends much of his time fishing from a rock, known as the “Wulver’s Stane.”

According to legend, the Wulver is very generous and would leave fish on the windowsills of poor families and those in need.

In times of illness or hardship, the Wulver was also known to guide lost travelers back to safety or help those who were struggling to find food.

In modern times, the Wulver can be seen as a symbol of the misunderstood outcast - those who, despite being different or feared by society, have much to offer in terms of kindness and generosity.

It’s a tale that resonates in today’s world, where judgments are often made based on appearance and where those who are different are too often ostracized or feared.

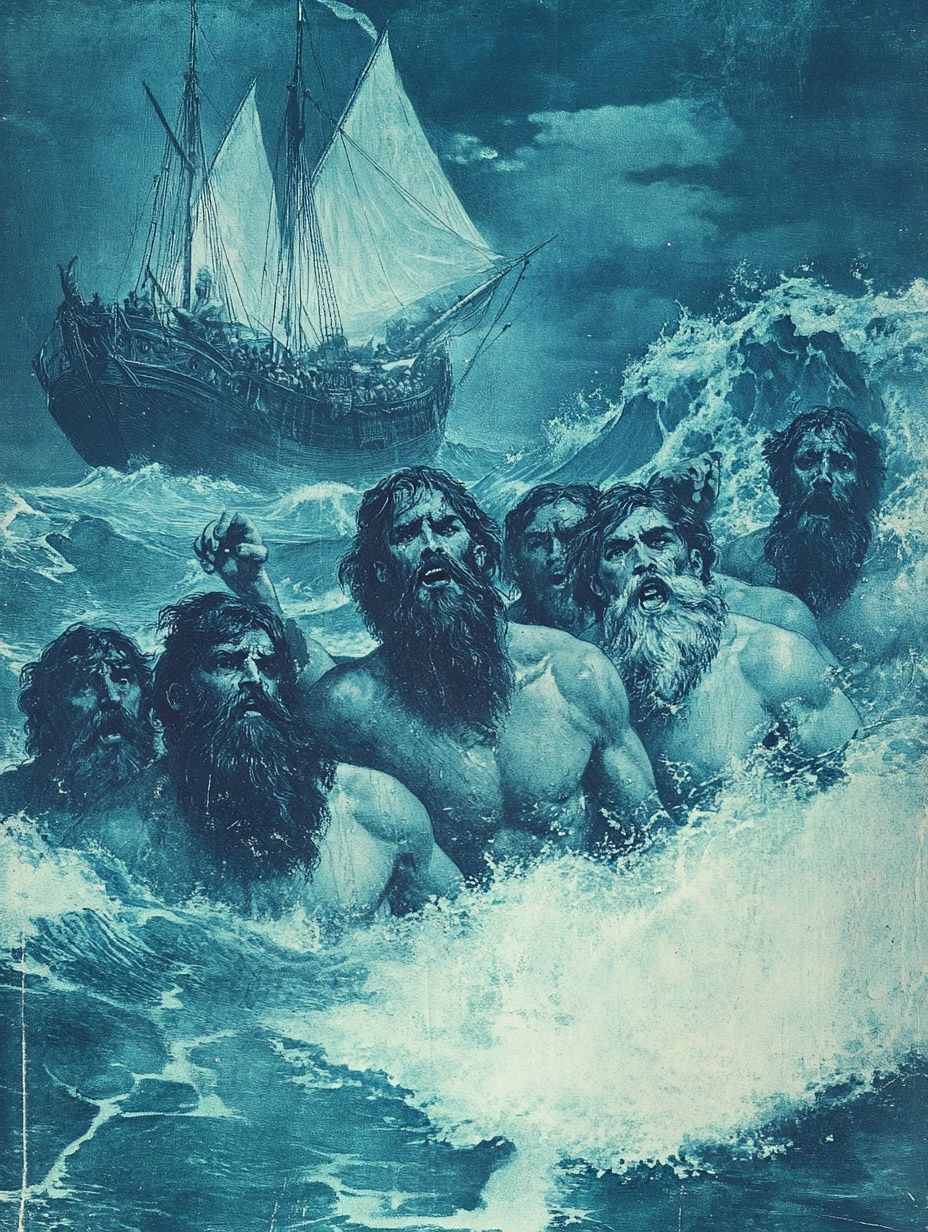

Blue Men of the Minch

The Blue Men of the Minch are unique figures in Scottish folklore. Sometimes referred to as storm kelpies, they’re said to live in the rough waters of the Minch, a strait that has claimed many ships over the centuries.

These mysterious beings are described as human-like in appearance but with blue-tinted skin and long, flowing beards and they travel in groups.

They’re strong swimmers and are often seen floating on or just below the surface of the water, waiting for ships to pass by.

Their goal? To create chaos. The Blue Men are known to challenge the captains of ships with rhyming riddles, demanding a quick-witted response.

If the captain cannot respond in kind, the Blue Men would summon storms, capsize the ship and drag it and its crew to the depths.

The stories of the Blue Men of the Minch probably originated from real fears held by sailors who navigated the dangerous waters of the region.

Cryptids

Loch Ness monster

The Loch Ness Monster, often nicknamed Nessie, is one of Scotland's most famous cryptids (and probably the world), said to inhabit Loch Ness, the largest and deepest freshwater loch in the United Kingdom.

Descriptions vary, but it’s often depicted as a long, serpentine animal with humps, a small head and a long neck resembling a plesiosaur. Sightings date back centuries, with one of the earliest reports coming from the 6th century when Saint Columba allegedly encountered a “water beast” in the loch.

The modern legend of Nessie began in 1933 after a couple reported seeing a large, mysterious creature crossing the road near the loch. This sparked widespread interest, leading to numerous sightings, photographs and even sonar scans over the years.

Some of the most famous evidence includes the 1934 “Surgeon’s Photograph” (later revealed as a hoax) and sonar readings from the 1970s and 1980s that detected large, moving objects under the water.

While many explanations for Nessie exist - ranging from misidentified animals like seals and sturgeon to geological effects and hoaxes - and despite extensive scientific investigations, no definitive proof has ever been found.

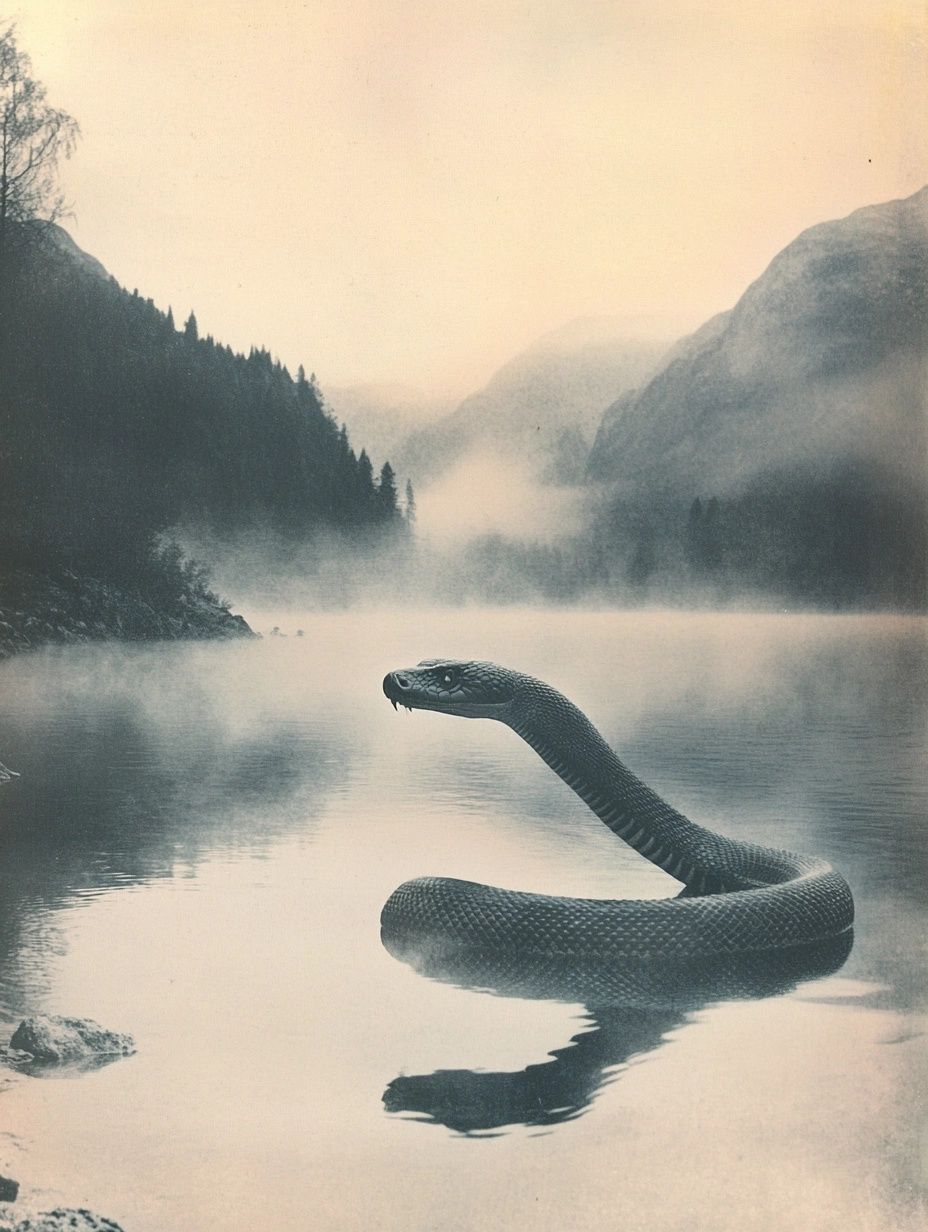

Morag

The Morag is another water cryptid, local to Loch Morar, a deep freshwater loch in Scotland and is often compared to the Loch Ness Monster, though it’s much lesser-known.

Descriptions of Morag vary, but it’s typically portrayed as a long, serpentine creature between 20 and 30 feet in length, with dark or brown skin, a snake-like head, and multiple humps visible above the water.

Unlike Nessie, sightings of Morag tend to describe a creature more serpentine or mammalian rather than dinosaur-like.

Morag’s legend includes numerous reported sightings dating back to the 19th century.

In one early account from 1887, James Macdonald described a creature in the loch that resembled a mermaid or kelpie rather than a traditional lake monster. More modern sightings include a notable encounter in 1948 when John Gillies, Noel O’Donnell and others claimed to see a 20-foot-long creature with distinct humps along the southern shore of Loch Morar.

Similarly, in 1969, Duncan McDonell and William Simpson reported striking Morag with their boat. They described it as a large, snake-like creature with humps and a head about 12 inches wide.

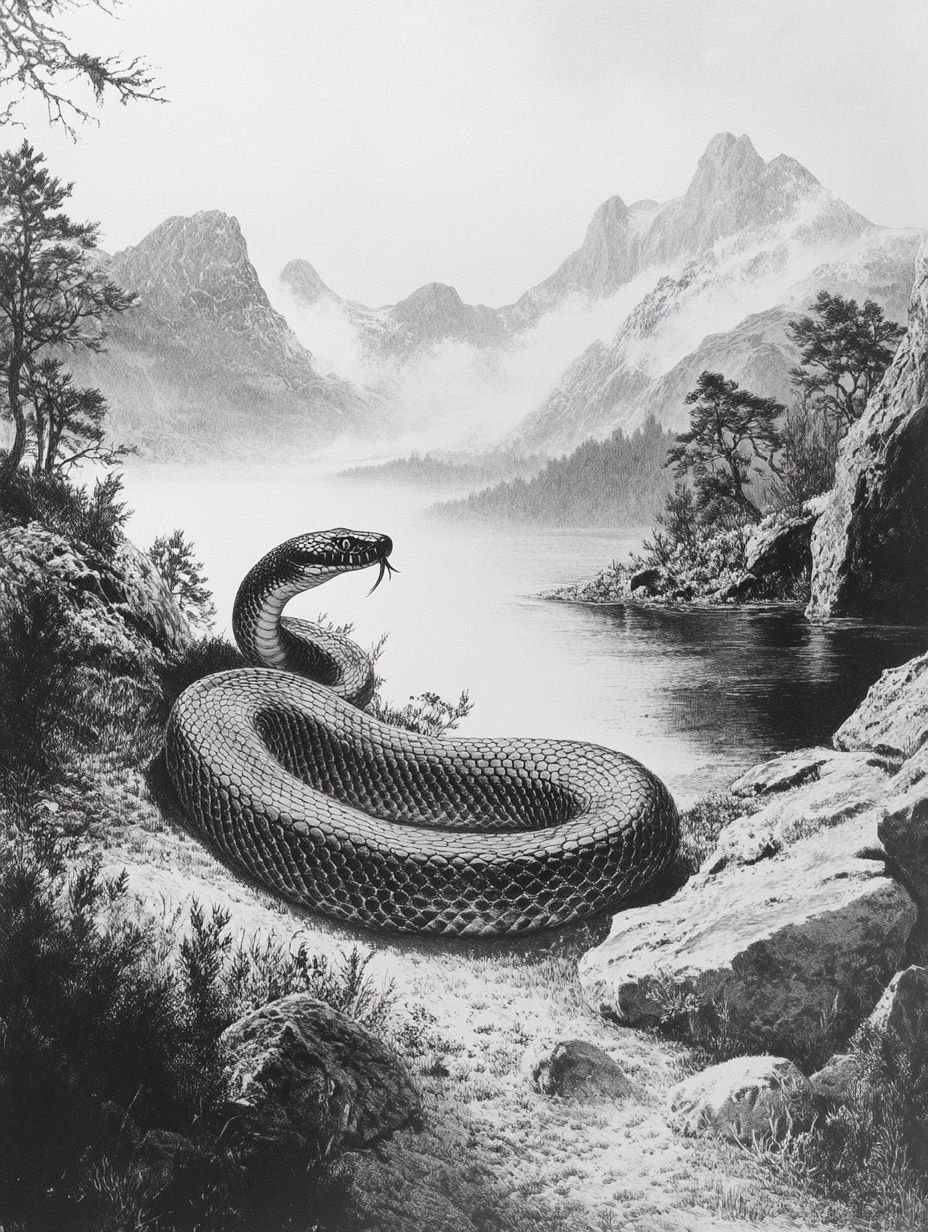

Beithir

Yet another Scottish water cryptid, the Beithir is a large serpent or water-dwelling creature, often described with a supernatural connotation.

The term “beithir” originates from Gaelic and Irish words meaning "serpent" or "beast." It’s said to inhabit lakes and caves, particularly around Loch a’ Mhuillidh in the Scottish Highlands. Descriptions of the Beithir suggest it is 9–10 feet long and most active during the summer months.

The Beithir is often portrayed as a water snake or dragon-like creature with an elusive nature. Unlike purely mythical beings, some sightings and local accounts align it more closely with a cryptid.

Possible explanations for the Beithir’s origins include misidentifications of large grass snakes, which occasionally grow up to 6 feet in Southern Europe but are smaller in the UK, or the European eel, which migrates to freshwater but rarely grows longer than 4 feet.

While the creature is rarely reported today, its legend remains an intriguing part of Scottish myth, combining the region’s rich folklore with cryptozoological curiosity.

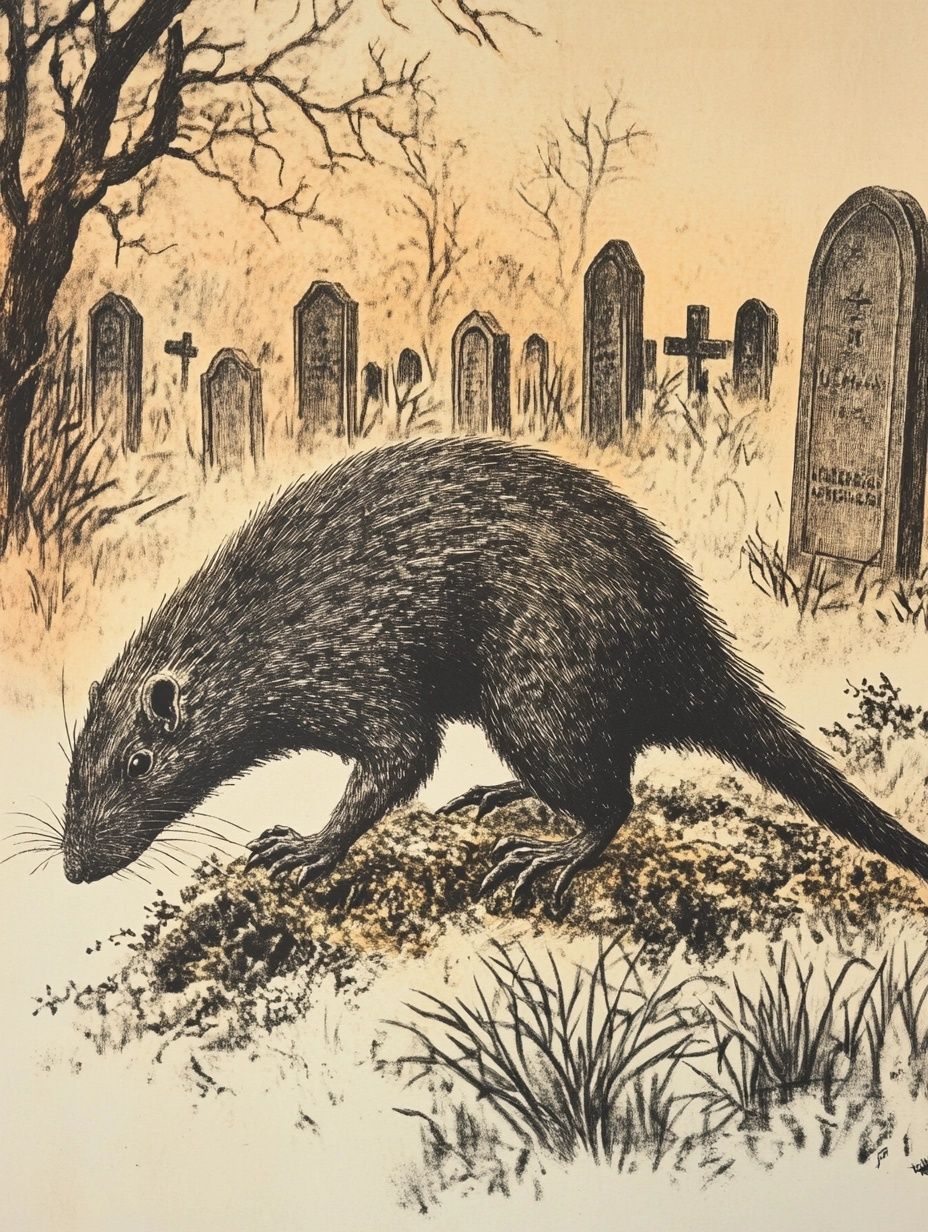

Earth Hound

The Earth Hound is a mysterious cryptid from Scottish folklore, described as a rodent-like animal with a long, dog-like head, a pig-like snout, large incisors, mole-like feet and a short, bushy tail.

It’s said to mostly inhabit graveyards where it burrows into graves and feeds on human corpses. Known by variant names such as Yard Dog or Yird Swine, the Earth Hound is firmly rooted in the folklore of Aberdeenshire.

Historical accounts of Earth Hound sightings are rare but intriguing. In one instance from 1867, a gardener reportedly plowed up an Earth Hound, which bit him before he killed it and brought its carcass home.

Another sighting occurred in 1915, when a similar creature was uncovered in the parish churchyard of Mastrick, Aberdeenshire. Witnesses described it as roughly the size of a rat but with mole-like features.

The Earth Hound's role in folklore likely stems from its association with death and burial practices, as well as a general fear of creatures disturbing the dead.

While its existence is not supported by science, these accounts capture the blend of curiosity and unease that surrounds many cryptids and mystery animals in Scottish culture.

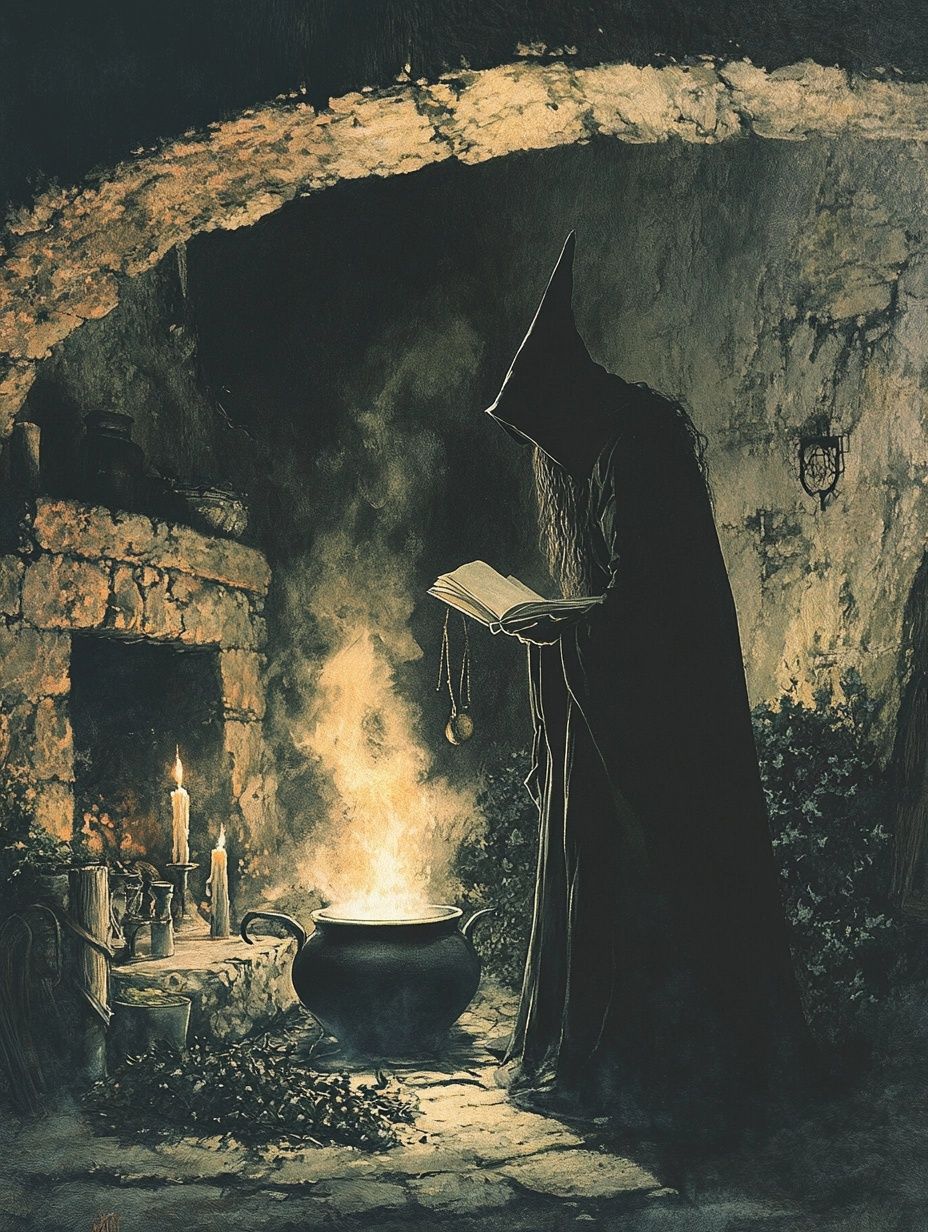

Witches in Scottish folklore

Superstitions around witchcraft hold a significant place in Scottish folklore.

Witches were believed to possess powers such as casting curses, controlling the weather, and shape-shifting, often linked to pacts with the Devil.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, witch trials, like the infamous North Berwick Witch Trials, reflected societal tensions and fears. These trials implicated alleged witches in a plot to sink the ship of James VI of Scotland with storms.

His personal involvement in these events deepened his fascination with witchcraft and influenced his efforts to address the perceived threat.

In 1597, James VI published Daemonologie, a treatise on witchcraft, demonology and possession, which legitimized the persecution of witches.

Scottish folklore often depicted witches as both feared figures capable of harm and misunderstood practitioners of folk medicine.

Stories of shape-shifting witches, such as the witch hare, highlight their dual role as villains and wise women.

James’s work and Scotland’s folklore reflect the complex attitudes toward witchcraft, balancing fear of dark magic with the remnants of ancient, practical knowledge.

Scottish legends

Scotland's rich folklore includes legends tied to historical events and supernatural encounters.

The famous story of Robert the Bruce and the Spider exemplifies perseverance, where the king, inspired by a spider repeatedly trying to spin its web, rallied his forces and triumphed at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

Similarly, the Maid of Norway tells of young Queen Margaret's death on her way to Scotland in the late 13th century, triggering the Wars of Independence and marking a turning point in Scottish history.

Another historical tale is the Battle of the Clans at Perth in 1396, where King Robert III organized a trial by combat between feuding clans, showcasing the fierce loyalty and martial traditions of Highland culture.

Supernatural tales add depth to Scotland’s legends, such as Michael Scott, a 13th-century scholar and magician known for his mystical powers, including commanding fairies and defeating a regenerating white serpent.

The Vision of the Dead from Nithsdale tells of a woman who cared for a fairy child and was later rewarded with a glimpse into the fairy world, revealing spirits of the dead and their moral consequences.

The Tale of Conall and the Thunder Hag offers a story of heroism, where Conall Curlew battled a destructive hag who set fire to the land with fireballs hurled from her chariot. Conall’s cunning and bravery allowed him to wound the hag and restore peace to the kingdom.

Fairy tales in Scottish folklore

Scottish fairy tales cover a wide variety of themes, from moral lessons to whimsical animal fables and tales of the supernatural.

Many stories explore cleverness and cunning, such as "The Fox Troubled with Fleas", where a fox outwits its tormentors, or "The Eagle and the Wren," which is about ingenuity over strength.

Others feature conversations between animals, like "The Frog and the Crow,", "The Fox and the Bagpipes" and "Rashin-Coatie" offering a blend of humor and folklore wisdom. These stories often reflect Scotland's natural landscapes, with creatures and characters tied to its hills, rivers, and forests.

Supernatural elements are also prominent, with stories such as "The Three Green Men of Glen Nevis". The tales often include moral underpinnings, cautioning against greed, pride, or dishonesty, while celebrating kindness and resourcefulness.

Scottish folklore is a treasure trove of stories that blend history, mystery and morality. These tales - whether they involve shape-shifting Selkies, the nasty Redcap or the elusive Loch Ness Monster - are a representation of Scotland's cultural and historical past.

They remind us of the complexities of human nature, the unpredictability of life and the ever-present tension between good and evil, nature and civilization.

As we go about our own lives, folklore tales like these can offer both caution and comfort, urging us to look beyond appearances, respect the world around us and find strength in our identities and traditions.

And who knows? Maybe there’s still a bit of magic left in the world after all.

Article sources

- Kotake, M. Heather. "Introduction to the Folklore of Scotland." (2014).

- Mackenzie, Donald Alexander, and John Duncan, illustrator. Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth & Legend. London: Blackie and Son, 1917.

- Gregor, Walter. Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North-East of Scotland. London: Folk-Lore Society, 1881.

- Fenton, Alexander, and David Heppell. “The Earth Hound: A Living Banffshire Belief.” Scottish Studies 31 (1992–1993): 145–146.

- Douglas, George Brisbane, Sir, ed. Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales. New York: Burt, 1900

More folklore from Scotland

From mystical animals to seeing the future, check out the best superstitions of old Scotland.

More folklore from around the world

Take a quick trip into the mystical and sometimes bizarre world of Portuguese folklore.

16 short tales from Indonesian folklore

Including the baby born from a cucumber - read about it now!

Greenlandic mythical creatures & folklore

The wild and remote wilderness of Greenland has created a series of fascinating folklore stories. Discover them here.