Global folklore’s creepiest sleep paralysis demons - the real imaginary stuff of our nightmares

In this article:

1. Ancient Legends & origins of sleep paralysis folklore

2.a. Asian sleep demon creatures

2.b. Middle Eastern sleep demon creatures

2.c Arctic sleep demon creatures

2.d African sleep demon creatures

3. Evolution of sleep paralysis folklore in Europe

a. Roots of the Mara sleep demon

b. The origin of the word “nightmare”

c. Regional Eastern European sleep demons

d. Protective measures against sleep demons

4. Humanoid and animal-like sleep demons

b. Animal & mischievous creature sleep demons

Sleep paralysis is an odd phenomenon that has been affecting people around the world for centuries. And though we now understand it scientifically, many cultures continue to interpret it through the lens of folklore and supernatural beliefs.

I started researching this topic after my own experience of sleep paralysis (just the one time and decidedly un-supernatural - but also incredibly unpleasant).

But having been through it, I can understand why so many would want to look to the paranormal to explain it.

So while I get the “science” I wanted to understand more about this subject from a folklore perspective and learn how cultures around the world have sought to explain sleep paralysis.

Here's what i found out about all the demons, spirits, witches and curses!

Updated: 8th Dec 2024

Author: Mythfolks

Ancient legends & the origins of sleep paralysis folklore

The phenomenon of sleep paralysis was recognised in the supernatural folklore of our most ancient civilizations.

Lilith (Ancient Sumerian):

The figure of Lilith can be traced back to ancient Sumerian texts as "Lilitu" or the "she-demon."

In some traditions, Lilith was believed to be Adam's first wife who became a demon after refusing to obey.

She was variously described as a vampire and a beautiful, alluring woman who trapped her lovers forever.

In later Hebraic traditions, she was depicted with serpent-like, scorpion, or dragon features. She was said to prey on men and women during the night, particularly during childbirth.

In modern Middle Eastern cultures, some women still wear protective amulets to ward off her influence.

Alu (Ancient Assyria):

In another example from ancient Mesopotamian culture, the Assyrians spoke of the "alu," an evil spirit that would attack people in their sleep.

Ephialtes (Ancient Greece):

Hippocrates is often attributed with one of the earliest known accounts (around 400 BC) of what we now recognize as symptoms of sleep paralysis.

He referred to the sensation of immobility and chest pressure but his writings didn't specifically isolate sleep paralysis as a unique condition, rather he saw it as part of his wider exploration of bodily and mental health.

However, while Hippocrates made an allusion to scientific theory, Greek mythology also introduced Ephialtes, meaning "to leap upon," a spirit thought to physically oppress sleepers and a way to explain those same sleep paralysis symptoms, supernaturally.

Incubus/Succubus (Ancient Rome):

The Romans adopted and expanded on these beliefs of the Sumerians and the Greeks with entities like the incubus, a male demon who drained energy from sleepers and the succubus, a female demon who preyed on men.

The first clinical recording of sleep paralysis

In the slightly more recent past, Dutch Physician Isbrand van Diemerbroeck is recognised as recording the first official clinical account of sleep paralysis in 1664, in his case study of a woman who experienced the sensation of an "Incubus or the Night-Mare."

His work reflected a shift toward a naturalistic and medical explanation of the phenomenon, separating it from purely spiritual or mythical interpretations.

Sleep demons, spirits and ghosts across Asia, Africa and beyond

Today, cultures around the world have developed their own versions of these nightmarish entities, each shaped by local beliefs and folklore.

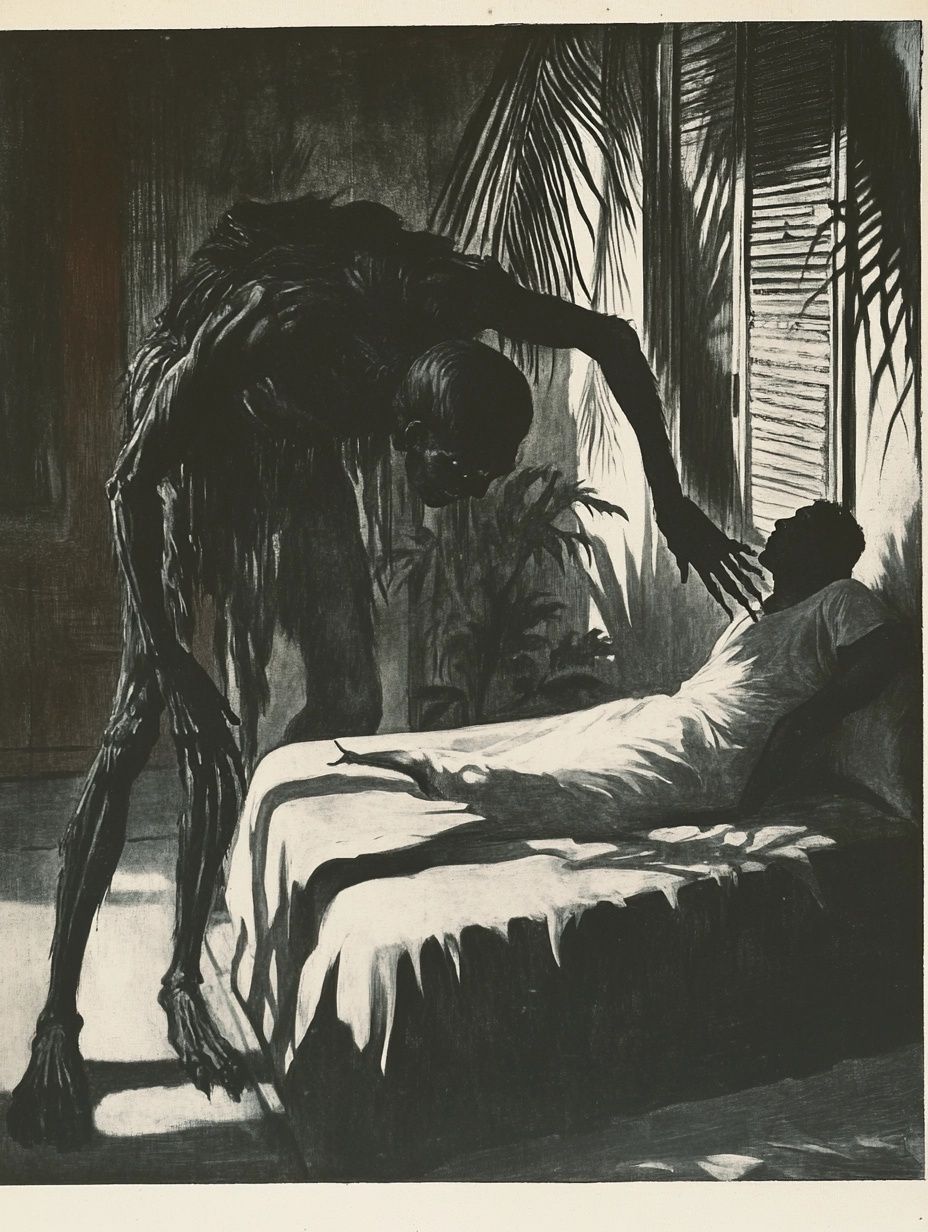

The most common type of sleep demon seems to be a sort of non-descript, spirit-like, shapeshifting being, a dark entity with a powerful crushing presence.

So i've split this article between those and then further down there's more info on the other more tangible human and animal-like creatures.

Asia in particular has a diverse history when it comes to folklore stories around sleep paralysis and some of the most well documented accounts.

Some of these legends below include darker themes, such as intrusive or violent acts, which I’ve chosen not to delve into here but you can always dig into these stories further if you’re interested in their deeper cultural context.

Asian sleep demon creatures

Khmaoch Sângkât (Cambodia):

Meaning "the ghost that pushes you down," Khmaoch Sângkât is a spirit from Cambodian folklore.

It became widely known during a study involving Cambodian refugees who survived the Khmer Rouge genocide.

Many of those affected reported seeing a ghostly figure resembling Khmer Rouge soldiers, with canine-like teeth, during sleep paralysis.

The spirit was often described in several forms, including a tall black shadow, a red-eyed figure dressed in Khmer Rouge attire, a simian-like demon, or a grotesque female head with internal organs exposed.

These experiences are often linked to past trauma and the connection between PTSD and sleep paralysis is thought to be bidirectional - it's thought that PTSD increases the likelihood of sleep paralysis, while sleep paralysis itself can trigger memories of past trauma.

Dab Tsog (Laos/Vietnam):

The Hmong are a traditionally animist people and the Dab Tsog is said to kill those who fall out of favor with the spirit world. For men in particular, the entity sits on the chest, strangling or suffocating them until they stop breathing.

In the 1970s and 1980s, dozens of Hmong refugees in the United States died in their sleep under mysterious circumstances, leading doctors to study what came to be known as Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS).

As researchers delved into the issue, they discovered a high prevalence of sleep disorders like sleep apnea, sleep paralysis and REM-related abnormalities in the community.

What made these cases distinct was the interaction between cultural beliefs, like Dab Tsog, and the physical symptoms that seemed to follow - with the deep rooted fear of an evil night spirit seemingly triggering or at least contributing to fatal outcomes

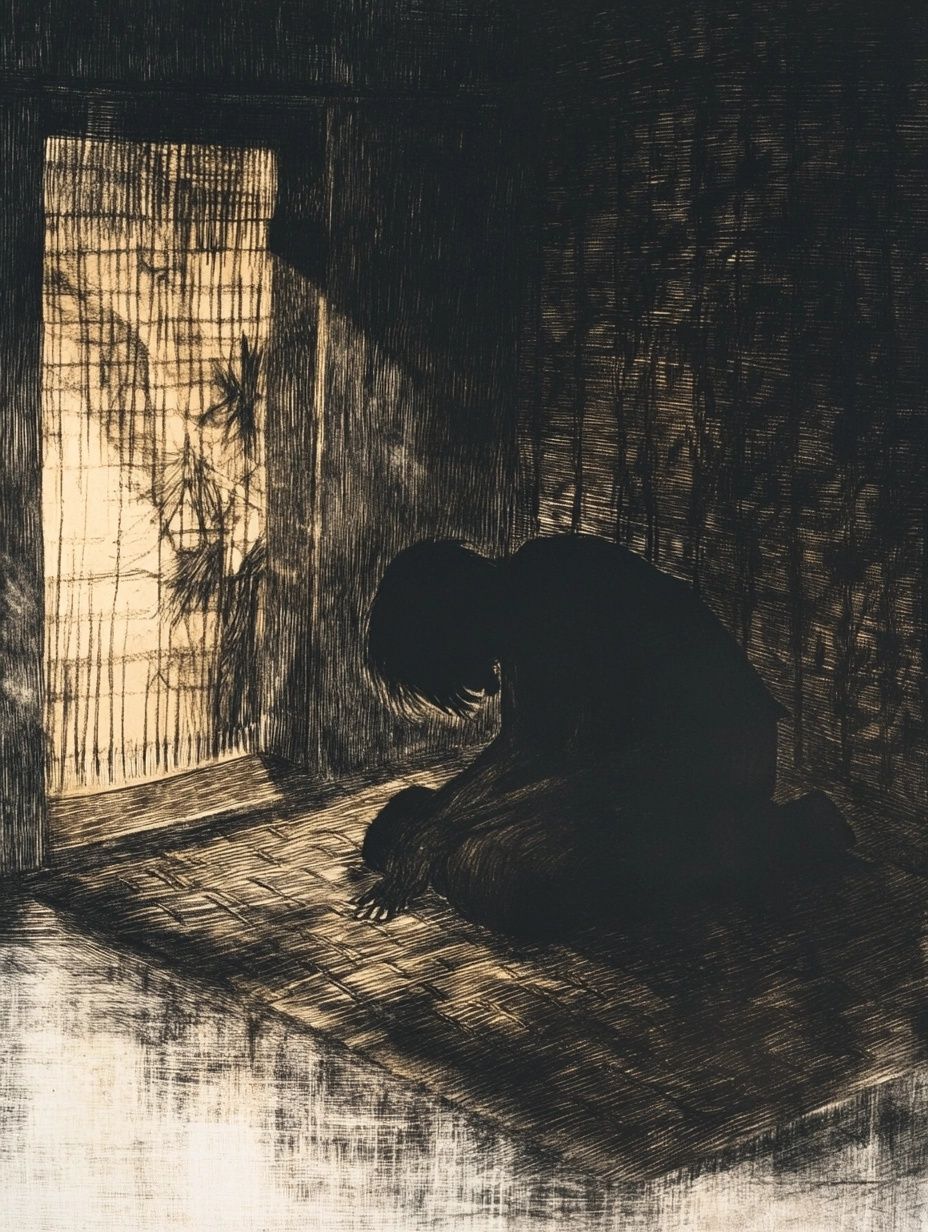

Kanashibari (Japan):

In Japan, the term "kanashibari" is used to describe sleep paralysis, which literally means "bound by metal chains."

Unlike the previous two stories, this phenomenon is often thought to be human-caused - a vengeful spirit summoned by Shamans - and is a common theme in Japanese folklore and popular culture.

Other stories of similar "pressing" or "sitting" demons around the continent include the Kwishin (South Korea), Phi Am (Thailand), while the Chinese are also said to believe in a kind of "ghost oppression" that causes immobilization between sleep and waking.

Middle Eastern Sleep Spirits

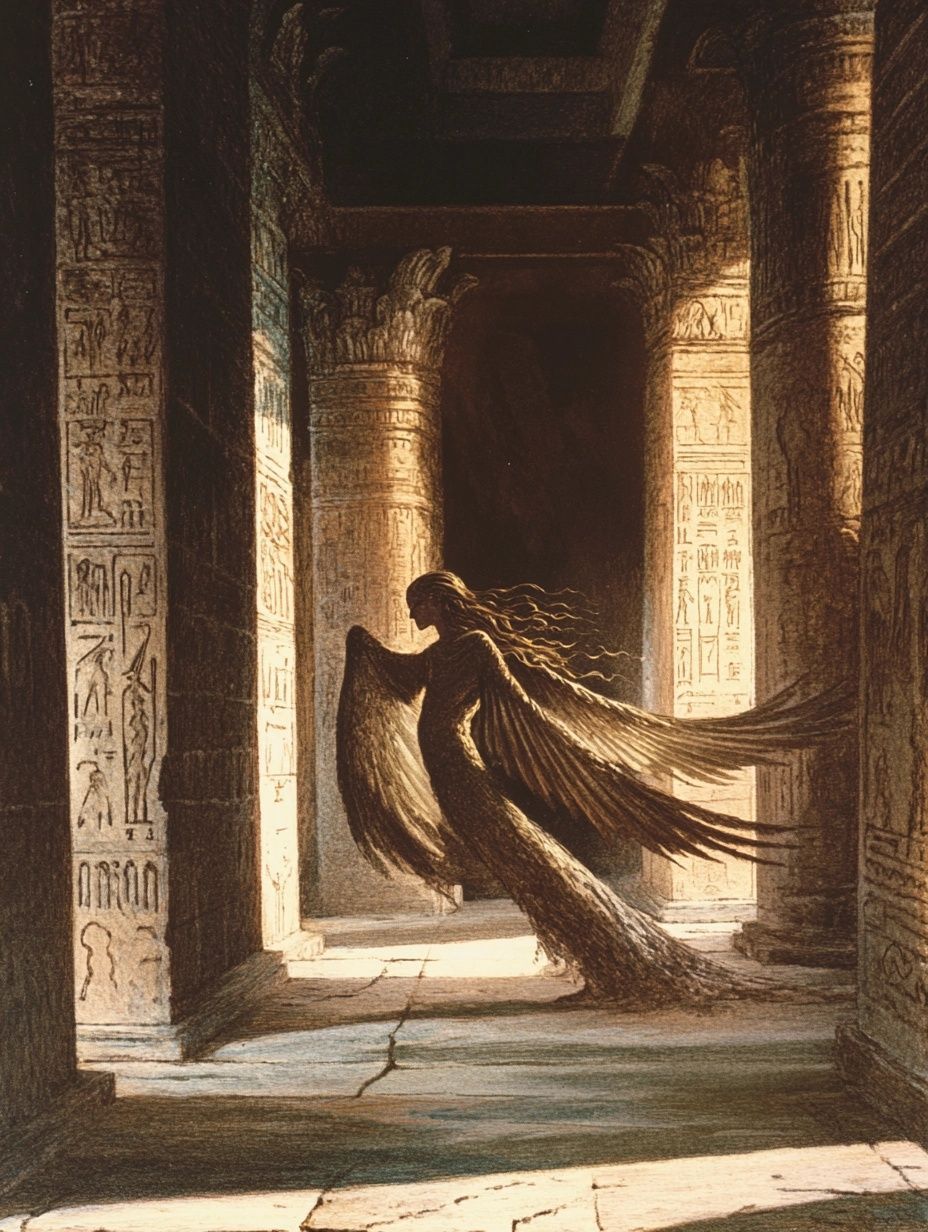

The Jinn (Egypt):

In the Middle East (and Egypt and other Muslim cultures), the Jinn are shape-shifting spirits, often depicted as smokeless flames or shadowy figures and appearing in sleep paralysis folklore.

The legend of the Jinn comes from Islamic teachings, where they are said to be beings created from fire who can be either good or evil.

Arctic sleep demon myths

Uqumangirniq (Inuit Canada)

Among the folklore of the Canadian Inuit, sleep paralysis is known as uqumangirniq, a phenomenon deeply tied to their spiritual beliefs. It's characterized by immobility, the inability to speak or scream, vivid hallucinations and the presence of a faceless or shapeless being.

Inuit tradition attributes uqumangirniq to the influence of angakkuit (shamans), who act as intermediaries between the spiritual and physical worlds.

While most shamans are considered benign, guiding rites of passage and interpreting dreams, some are believed to use their powers in conflicts.

Through spells known as ilisiiqsijuq, rival shamans can spiritually attack their enemies during sleep, exploiting the fragile connection between body and soul (tarniq).

In the most extreme cases, this severing of the tarniq is thought to result in death, making uqumangirniq a deeply feared occurrence in Inuit culture.

African sleep demon entities

Ogun Oru (Nigeria):

In southwest Nigeria, the Yoruba people refer to sleep paralysis as "ogun oru," or "nocturnal warfare." It's mostly experienced by women and is influenced by the belief in a rivalry between a spirit husband, called "oko orun," and an earthly husband.

The spirit husband, often described as a water-like being, is believed to intrude on the sleeper and carry out violent acts. People try to treat it with Christian prayers or traditional rituals to get rid of the demon.

Dukak (Ethiopia)

The Dukak is a similarly evil spirit that haunts vulnerable sleepers. It's often described as a small, dark creature.

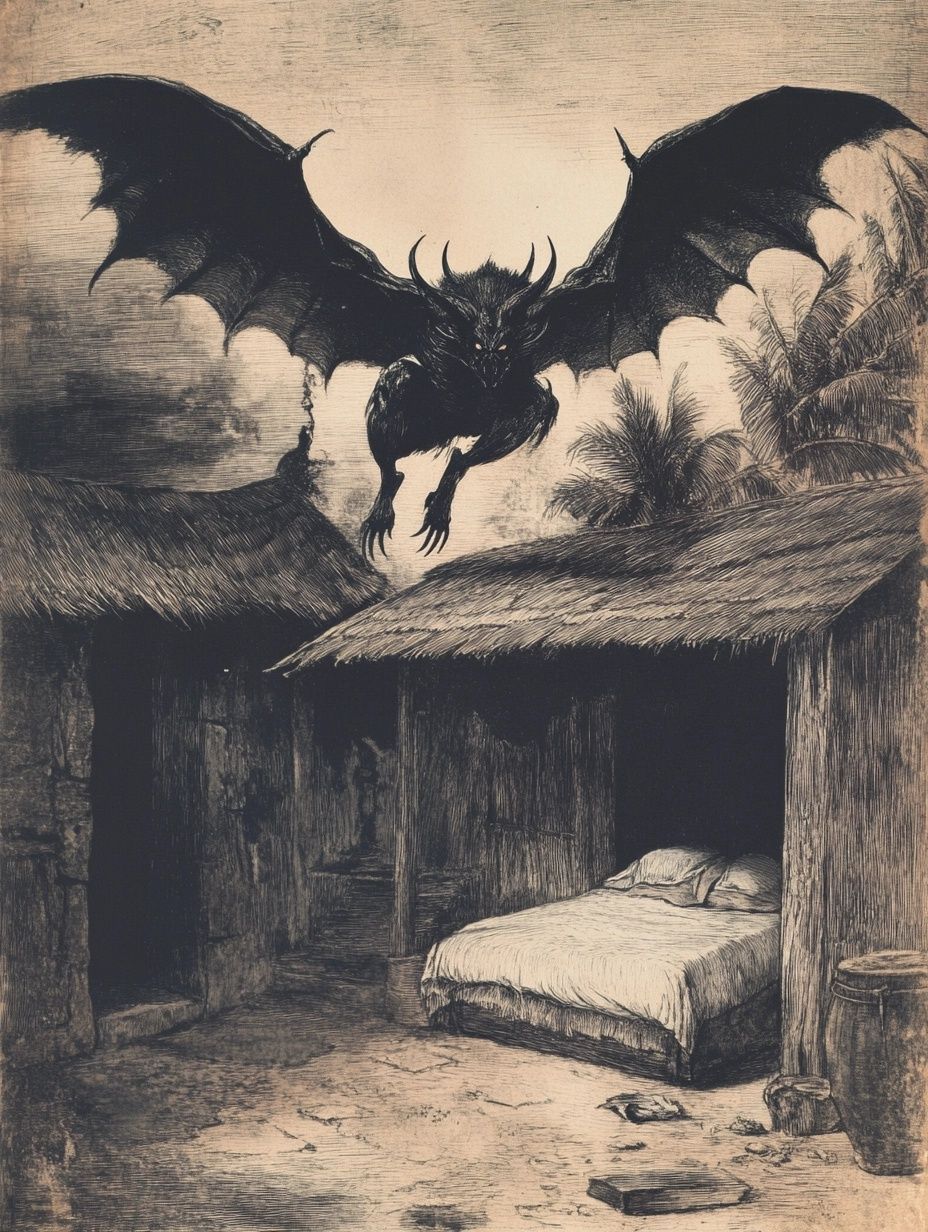

The Popobawa (Zanzibar)

Meaning "bat-wing" in Swahili, Popobawa is a shapeshifting entity from Zanzibar’s folklore, first reported in the 1970s during a period of political unrest.

Unlike other sleep paralysis creatures, it's said to physically attack its victims.

Often described as a shadowy figure with bat-like wings, the Popobawa is closely tied to societal chaos, emerging during times of upheaval and spreading fear through communities, where people stay awake together for safety.

The Mara and the evolution of sleep paralysis folklore in Europe

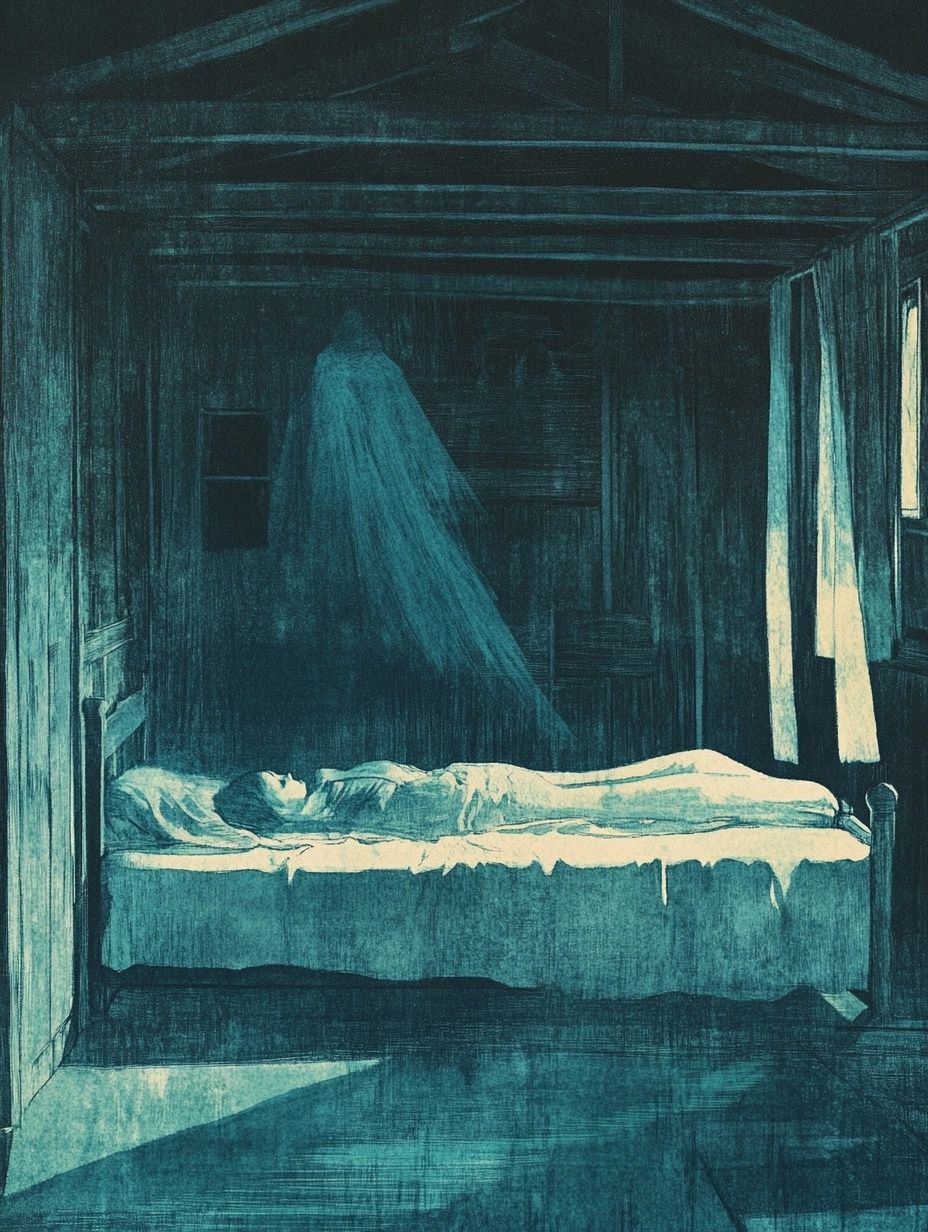

Across Europe, the folklore of nocturnal spirits tied to sleep paralysis revolves around the Mara and its many regional counterparts.

Over time, these beliefs spread across Europe, influencing both local folklore and language, leaving a lasting legacy in the words used for "nightmare" and the stories of supernatural oppression.

Scandinavian and Germanic Roots of the Mara sleep demon

The Mara first appears in Norse mythology as a restless spirit or demon tied to unresolved grievances or envy. It was said to visit sleepers, sitting on their chests to torment them with oppressive nightmares.

In Swedish folklore, protective charms and specific sleeping rituals were used to fend off the Mara.

This fear of nocturnal attack was shared across Germanic cultures, where similar entities appear, such as the Mahr in Old High German and the Mare in Middle Dutch.

These stories cemented the image of a chest-pressing spirit as a common fear in early European societies, directly linking folklore to the experience of sleep paralysis.

The origin of the word “nightmare” in sleep paralysis folklore

The term "mare", central to these myths, became embedded in European languages, shaping how cultures conceptualized and named nocturnal terrors.

In English, the word evolved into "nightmare," blending “night” with “mare” to describe both the frightening dreams and the oppressive spirit behind them.

Similarly, in German, the term became "nachtmahr," retaining its connection to the supernatural tormentor.

In French, the cauchemar - from "caucher" (to trample) and "mare" (spirit) - added a new dimension to the myth, describing a trampling entity responsible for suffocating sleepers.

As French culture and language spread during the 19th century, cauchemar influenced other European languages, such as Russian (кошмар) and Polish (koszmar).

These borrowed words carried the same connotations of supernatural oppression, tying the linguistic evolution of "mare" to the shared European fear of sleep paralysis spirits.

Regional Eastern European sleep demons

As the legend of the Mara spread, it adapted to local cultures, creating unique yet connected variations of the same creature.

Zmora (Poland):

A shadowy figure believed to be the spirit of a vengeful or envious person.

Mora (Bosnia)

In Bosnian folklore, the Mora attacked by sitting on the sleeper’s chest.

Nocnitsa (Russia)

Known as the “Night Hag,” the Nocnitsa was feared for tormenting children during sleep.

Morava (Czech Republic and Slovakia)

This spectral figure was tied to the restless dead, disturbing sleepers with unresolved grievances.

Moroi (Romania)

In Romanian folklore, the Moroi is a restless spirit with vampiric characteristics. While it's not solely linked to sleep paralysis, it shares traits that blend with the Mara archetype.

Many of these cultures also have idioms and expressions related to sleep paralysis entities. Phrases like “pale as a zmora” or “dragging like a zmora” reflect the influence of these folklore figures in daily language, showing how deeply ingrained these beliefs are in cultural consciousness.

Protective measures against sleep demons in European cultures

Protective rituals were common across these cultures, often aimed at distracting the creature:

Counting tasks: Similar to other folklore entities, the Mara or variations of can be compelled to complete impossible tasks to distract or ward off the creature from entering the home.

For example, the spell to ward off the Mora in Bosnia involves instructing the spirit to count the leaves in a forest or fish in a river, making it impossible for the spirit to complete its task and continue tormenting the sleeper.

Charms and objects: Placing sharp objects, brooms, or holy symbols near the sleeper is meant to deter the entity.

Spiritual or religious rituals: Spells to repel beings associated with sleep paralysis are variously described.

This synthesis showcases the similarities and local adaptations of the Mara and its variants, reflecting shared cultural fears of nighttime vulnerability.

Humanoid and animal-like sleep demons from around the world

As referenced earlier, the majority of stories about sleep paralysis creatures feature beings that are more spirit like and often have shapeshifting ability, like all the ones i've just covered.

But there are still more types of nightmare creatures that are often described more tangibly.

Witch-like sleep demons from Latin & North America

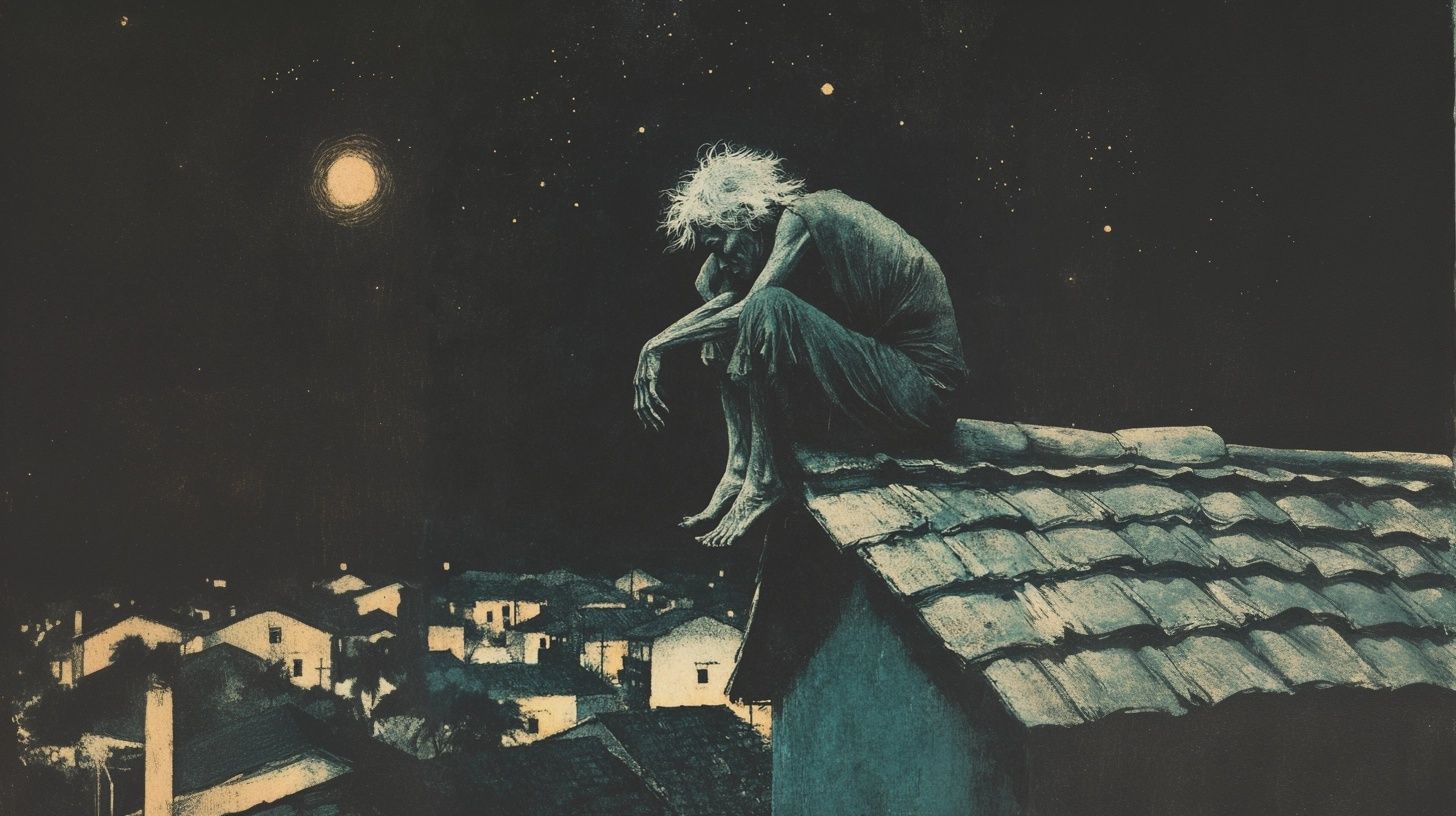

Pisadeira (Brazil)

La Pisadeira is a witchy sleep demon creature in Brazilian folklore that appears at night and targets those who eat too much before bed, or sleep on their backs, causing them to have terrifying dreams.

Old Hag (Canada)

The Old Hag is a Newfoundland legend from Canadian folklore, imagined as a witch-like figure that sits on the chest of the sleeper.

Pandafeche (Italy)

In the Abruzzo region of Italy, the Pandafeche is a creature often associated with sleep paralysis. It's usually described as an evil witch (but sometimes a ghost or a black cat-like creature).

The Pandafeche is believed to have ill intentions and folklore also suggests that these witches can transform into cats or may even be the souls of people who died violent deaths.

To prevent a Pandafeche attack, some people place a broom upside down by the bedroom door, as the witch is said to become distracted by counting the broom's bristles.

Animal & mischievous creature sleep demons

Pesanta (Catalonia, Spain)

The Pesanta is usually depicted as a large black dog or cat that enters homes at night and steps on people's chests, causing difficulty breathing and nightmares. It's said to have holes in its paws - just like the next creature.

Fradinho da Mão Furada (Portugal)

Fradinho da Mão Furada, or “Little Hand-Hole Friar,” is a small friar with a red cap who sneaks into bedrooms through keyholes.

He sits on the chest of those who sleep after heavy meals. This Portuguese legend is considered the origin of Brazil’s Pisadeira, blending elements of mischief and terror to create its haunting presence.

Alp (Germany)

Is a similar sleep creature German legend that creeps in through the keyhole in a door.

Tokoloshe (South Africa)

In some South African cultural groups, sleep paralysis is attributed to a phenomenon known as the "Segatelelo assault," believed to be caused by black magic and demonic dwarf-like creatures called the "Tokoloshe."

The Tokoloshe is feared as an evil spirit that is summoned to torment or harm individuals, often linked to sleep disturbances similar to sleep paralysis.

Kijimuna (Japan)

Alongside the Kanashibari, the Kijimuna is another mischievous spirit in Japanese folklore, known for causing disturbances during sleep.

It is often described as a small, red-haired creature that creates a sense of suffocation.

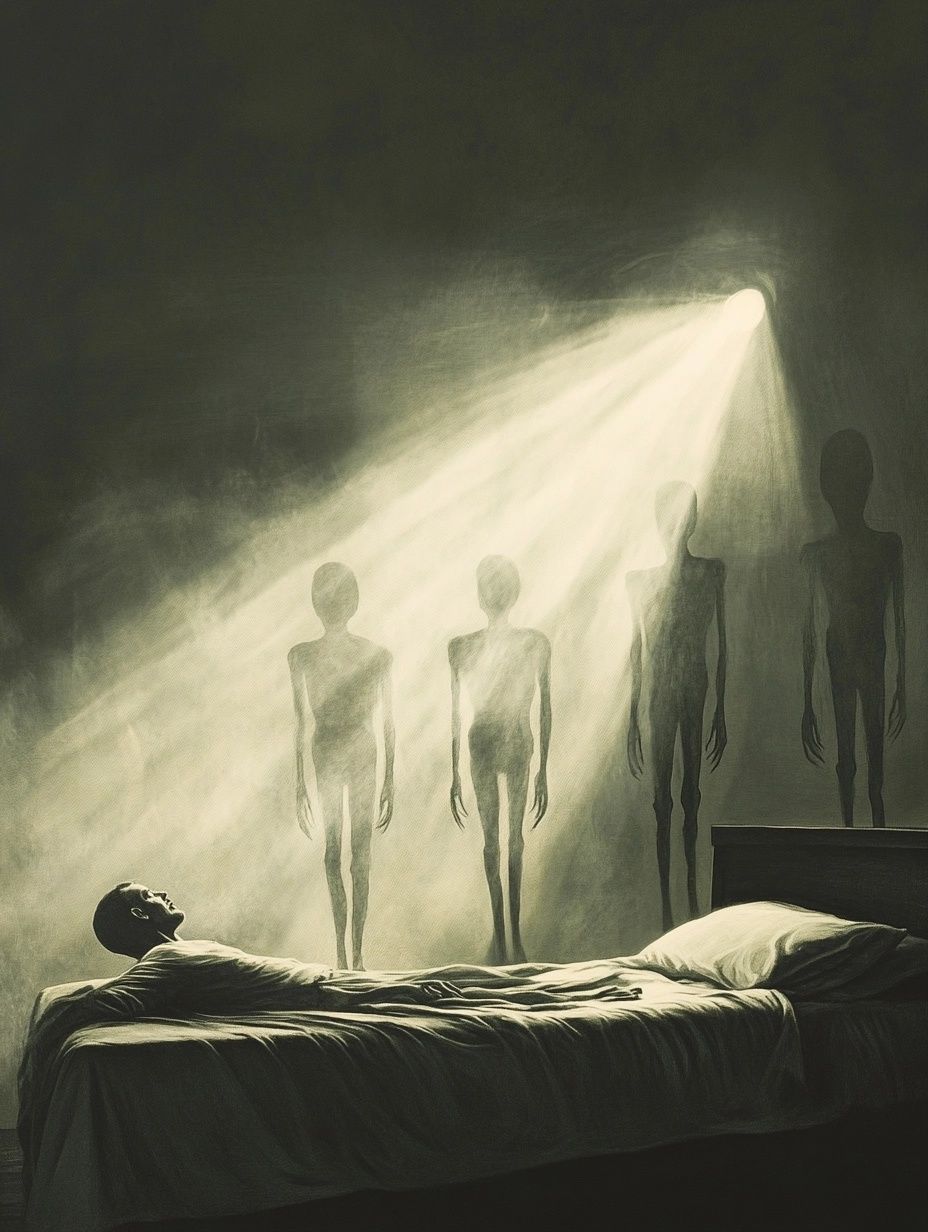

Alien abductions and sleep paralysis

In modern times, the phenomenon of sleep paralysis has been linked to alien abduction narratives in North America.

Many abduction accounts share striking similarities with sleep paralysis experiences - immobility, the sensation of a threatening presence, vivid hallucinations of lights or strange beings.

The rise of alien abduction stories in popular culture, particularly following events like the alleged Roswell UFO crash in 1947 and the widely publicized accounts of Barney and Betty Hill in 1961, helped shape this modern folklore.

Artists and media further solidified the image of alien abductors as bald, large-headed humanoids with elongated eyes, a depiction that continues to influence these narratives.

Research suggests that many abduction experiences may stem from sleep paralysis episodes combined with false memories implanted during hypnosis, highlighting how cultural imagination and biological phenomena intersect to create compelling stories.

A first-hand account of a sleep paralysis episode

I referenced in the intro that i started looking at this subject following an experience with sleep paralysis. I’d accidentally fallen asleep on the sofa one Saturday afternoon watching some snooker (for most people this will seem a natural outcome of watching snooker!).

I was asleep for maybe an hour but I suddenly woke, acutely aware I could still hear the TV and see the room ahead of me, but I was completely unable to move.

My mind started to go into mild panic, I felt really awake but nothing was making sense. I remember vividly trying to move my arms but they simply would not respond and I suddenly became conscious of breathing and how to breathe and was I breathing enough - cue more serious panic.

There wasn’t any creepy being sitting on me or talking to me and I put that down to my overly rational mind and the fact that I haven’t grown up in a culture that has these stories deeply engrained into everyday lives. I'd barely even heard of sleep paralysis before it happened.

I don’t know how long it lasted, it might have only been a minute, it felt like an hour. But at some point I woke up properly, mighty relieved. And now that I’ve experienced it, I’m always wondering if will randomly strike again (but so far, touch wood, not yet).

As frightening as these nightmare beasts are, they all point to something universal in the human experience: our tendency to personify our fears and anxieties.

Sleep paralysis is terrifying because it’s a loss of control - a moment when our bodies betray us and our minds seem to turn against us. And what better way to explain that sensation than by blaming it on something external, something monstrous?

Today of course, we know a lot more about sleep paralysis, though I was quite surprised to learn that only about 8% of people are estimated to have experienced it (although another source says between 1.4% and 40% so who really knows?!).

Just like my experience, it’s a state where the brain wakes up but the body remains “locked” in REM sleep, unable to move. The accompanying hallucinations - if they occur - are the mind’s way of trying to make sense of this disconnect.

But despite our scientific understanding, and although my own experience was rather bland by comparison, the folklore figures I discussed above will continue to resonate across the world. They give shape to the formless, turning personal fears into shared stories.

And as long we keep experiencing that crazy moment of waking up, but actually waking up, I suspect the Mara, the Popobawa and their nightmarish cousins will never truly disappear.

For now, next time you wake up at 3 a.m. and can’t move, take comfort - at least you’re not alone.

Article sources

De Sa, Jose FR, and Sérgio A. Mota-Rolim. "Sleep paralysis in Brazilian folklore and other cultures: A brief review." Frontiers in psychology 7 (2016): 1294.

Cox, Ann M. "Sleep paralysis and folklore." JRSM open 6, no. 7 (2015): 2054270415598091.

Povetkina, Polina B. "Sleep paralysis: At intersection of biology and folklore." RUDN Journal of Studies in Literature and Journalism 27, no. 3 (2022): 514-522.

Jalal, Baland, Andrea Romanelli, and Devon E. Hinton. "Sleep paralysis in Italy: Frequency, hallucinatory experiences, and other features." Transcultural Psychiatry 58, no. 3 (2021): 427-439.

Jalal, Baland, H. Sevde Eskici, Ceren Acarturk, and Devon E. Hinton. "Beliefs about sleep paralysis in Turkey: Karabasan attack." Transcultural Psychiatry 58, no. 3 (2021): 414-426.

Johnson, Cyle. "Sleep Paralysis: A Brief Overview of the Intersections of Neurophysiology and Culture." American Journal of Psychiatry Residents' Journal (2023)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562322/#:~:text=The%20prevalence%20of%20sleep%20paralysis,%2C%20adolescence%2C%20or%20young%20adulthood

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3616878/

You might also like